Mapping Doggerland#

Vince Gaffney and Simon Fitch, University of Birmingham#

|

Global warming at the end of the last Ice Age led to the inundation of vast landscapes that had once been home to thousands of people. Amongst the most significant of these is Doggerland, occupying much of the North Sea basin between continental Europe and Britain. At the opening of the Holocene, Doggerland was still a large ‘country’ of hills, plains and river valleys, with an extensive coastline. Over a period of more than 4000 years this landscape was progressively lost to rising sea levels, so that by around 5500 cal BC Britain had become an island and the geography of north-west Europe approximated its present configuration. It was perhaps not until the publication of Bryony Coles’ Doggerland: a Speculative Survey in 1998 that the importance of this submerged landscape was brought home to the current generation of researchers; indeed it was Coles who gave Doggerland its name (after the wellknown submarine banks). Before Coles’ seminal paper, archaeologists had tended to envisage Doggerland simply as a land-bridge but Coles rightly asserted that the area should more correctly be seen as an inhabited landscape in its own right, and indeed one that is likely to have played a central role in the early prehistory of north-west Europe. Although it was recognised that these landscapes had the capacity to retain and preserve archaeological evidence that might be rare or absent within contemporary terrestrial contexts, the relevant deposits are often masked by tens of metres of water or sediment and they provide archaeologists and heritage managers with a unique set of technical and methodological challenges.

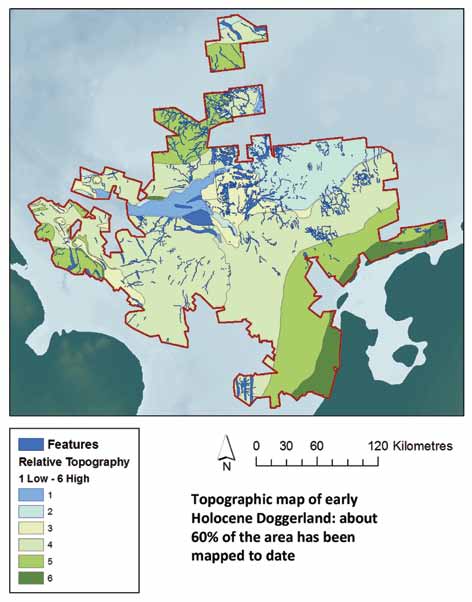

Over the last decade researchers at the University of Birmingham have pioneered the development of techniques which use seismic reflection data, gathered in particular for oil exploration at an overall cost of hundreds of millions of dollars, to map submerged Holocene (and Late Pleistocene) landscapes, with notable success (Gaffney et al 2007; 2009). The North Sea Palaeolandscapes Project (NSPP), funded through English Heritage, the Marine Aggregates Sustainability Fund and NOAA (National Geophysical Data Centre), achieved approximately 60% mapping coverage (c 45,000km2) of the area likely to have formed the landmass of Early Holocene Doggerland in the southern North Sea, using data provided by PGS (Petroleum Geo-Services – http://www.pgs.com/ ) from their ‘Southern North Sea Mega Merge’, along with additional information provided through the Geological Survey of the Netherlands (http://www.en.geologicalsurvey.nl/

) from their ‘Southern North Sea Mega Merge’, along with additional information provided through the Geological Survey of the Netherlands (http://www.en.geologicalsurvey.nl/ ). The Humber Regional Environmental Characterisation project (Humber REC), a collaboration between the Birmingham team and the British Geological Survey (Tappin et al 2011), included ‘ground truthing’ of interpretations of the seismic datasets, through the targeted recovery and palaeoenvironmental analysis of sediment cores from features previously identified as palaeochannels (Gaffney et al 2007). Together these data provide our best guide to the outline of Mesolithic Doggerland and its environment and the same methodologies have been applied to other, similar areas around the British Isles. The results of this work are now being used as the basis for further palaeoenvironmental and behavioural modelling to guide future exploration of these enigmatic and globally important landscapes (Ch’ng and Gaffney forthcoming).

). The Humber Regional Environmental Characterisation project (Humber REC), a collaboration between the Birmingham team and the British Geological Survey (Tappin et al 2011), included ‘ground truthing’ of interpretations of the seismic datasets, through the targeted recovery and palaeoenvironmental analysis of sediment cores from features previously identified as palaeochannels (Gaffney et al 2007). Together these data provide our best guide to the outline of Mesolithic Doggerland and its environment and the same methodologies have been applied to other, similar areas around the British Isles. The results of this work are now being used as the basis for further palaeoenvironmental and behavioural modelling to guide future exploration of these enigmatic and globally important landscapes (Ch’ng and Gaffney forthcoming).