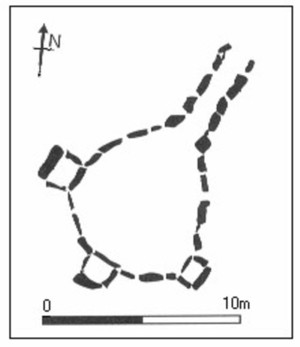

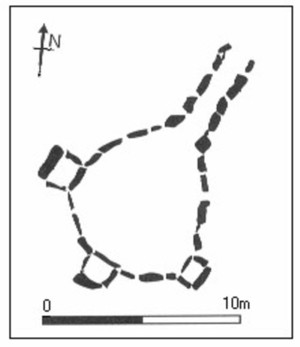

Figure 1: Plan of the orthostats of Fourknocks 1, Co. Meath, Ireland. (after Cooney and Grogan 1992 Irish Prehistory a Social Perspective Wordwell. p. 68)

I'll make my report as if I told a story, for I was taught as a child

that Truth is a matter of the imagination. The soundest fact may fail or prevail in the style of its telling: like that singular organic jewel of our seas, which grows brighter as one woman wears it and, worn by another, dulls and goes to dust. Facts are no more solid, coherent, round, and real than pearls are. But both are sensitive (LeGuin 1969, 9).

The signpost said it was the next exit, 'Fourknocks 12km'. Startled by the difference that the bypass made to her approach to the site she remembered her first visit nearly 20 years before, thinking, 'I wonder how he's doing these days?' Leaving the motorway she took more notice of the subtle changes that had happened in that time - a new house at that crossroads, that one abandoned - and thought about how rarely those kinds of changes turn up in the Excavations Bulletin.

This self-conscious pondering, an abiding character flaw, had been exacerbated by the conference. Yes, it had been good, but she was unsatisfied. With all the changes in archaeology since the 1960's people still behaved as if explaining or exploring the past was vitally important without considering what it was important for.

In fairness, she thought, some academics had come clean and admitted that it was valuable because it was fun. And the heritage managers talked about 'preserving the past for our future'. But the people who had conducted the 'mitigation' for the motorway she had just left were clear that recording was not the same as preserving and expressed the usual frustration that bureaucracy buried most of their records as surely as the tarmac buried sites. Of course, each group was preaching to the converted since few had crossed the chasms that divided the 'discipline'- or should that be 'vocation' or maybe again 'industry'? And she longed for these goals to be apparent in the papers presented.

When the conference was over she was relieved to have taken an extra day to return to the site where she had first pursued her own desire in archaeological research. She felt sure that being there would remind her of what she herself found valuable in 'the pursuit of the past' and help her make the decision that was weighing on her mind.

The engine did not strain in climbing the hill and she smiled remembering the encouragement her scooter had needed to make the ascent. Collecting the key from Mrs. White, she promised to return it before dark. She nearly asked the guardian how often she visited the site herself and what she felt about it but caught herself. These days it would sound too much like an inspector checking up. Besides, her decision had to be based on her own connections with the place.

The first glimpse of the site surprised her as always. The reconstructed mound of the passage tomb always looked so small when approached from the south. That was part of the magical sense that it was bigger on the inside than it was on the outside. But would it be big enough for her doubts and disagreements as well as her delights and desires? There was only one way to find out.

As soon as she opened the door she could see that there was something lying on the floor at the junction of the passage and the chamber. It was a small box that sprang open as she picked it up. The springing figure bounced around nearly as surprised as she was. Yes, this was how she felt. 'Having sprung free of the epistemic and technical constraints of the 1960's we are free to pursue any line of research' she thought, 'But some of us have been left with the rather undignified stance of a jack in the box'.

While scholars in the 1960's had disagreed over the right approach to archaeology, they had agreed that there was a 'right' way. Even when she had been an undergraduate there had still been an overwhelming concern with a unified methodology and theory. Now she just laughed at any sentence which began 'archaeologists agree

' Most people settle into a niche, or was it a faction? The times when her commitment to archaeology felt weakest were when she was asked which group she belonged to.

She remembered debating Hawkes' ladder of inference with classmates. It felt good to have left such ordered and orderly progressions behind. Undergraduates were now taught that the main limit to understanding is the source of the desire to know and the questions that flow from it. The understanding of things like diet have been increasingly questioned while other research stretched from the top of Hawkes' ladder towards sexuality, dissent and other topics once thought safely out of reach.

The grand projects to explain humanity or reconstruct history held imperatives for young scholars - organise the typology of that set of artefacts! Sort out that tricky bit of chronology! Explain that confusing stage in cultural development! Having abandoned unilinear progression as an explanatory framework for the past, how should she move forward in her own career? To answer this she needed purpose. 'I need to know why I enjoy doing archaeological work and why people are prepared to pay me to do it' she had muttered earnestly at the end of an evening.

Bringing her mind back to the place she was, she moved to the eastern alcove. Unadorned, it always drew her first. There was a fragment of pottery lying on the sill, the rim of a willow pattern plate. As she picked up the broken plate she was a small child again. She found it in two pieces in the base of the hedge at the bottom of the garden. It was autumn and the dirt chilled her fingers. She brought the plate inside, demanding that it be made whole. Her breath caught now at the clarity of her earliest memory.

For years this memory had given her a sense that she was predisposed to her profession. More recently she considered the emotional impact of a yearning to fix everything. The negotiation of multiple pasts and the weaving of explanatory systems from them are tasks that offer many opportunities to glue people and things together.

The first approach to the past is through memory. People use memory to construct identity, to form relationships between people and things, to learn. This use of the past as memory is an essential human characteristic. Politically this makes the past very powerful and working with the narratives of the distant past is a central function within any society.

Indeed, the terrifying political uses of the past often made her work difficult. So many people wanted to equate increased social ranking with progress, or use the results of archaeology to affirm their right to present social dominance. Few enough people shared her political convictions. She didn't want to speak only to them and couldn't hope to 'convert' the rest. Archaeologists had been long aware of the political impact of their work. That didn't stop the powerful from writing the past in their own image.

But this very difficulty showed that doing archaeology well is important. The past is an exciting if dangerous field of enquiry but obviously archaeologists aren't the only people to work with the past. Why work in archaeology with its squabbling theorists, pedantic bureaucrats, poor pay and cold mornings? She peered more deeply into the alcove, hoping to move beyond a need for the past to a need for archaeology.

Yes. There was another childhood fragment, a shape sorter. Her own first encounters with this toy were forgotten but it called to mind so many other children's screams of frustration and squeals of triumph that its answer to her question was obvious. The shape sorter teaches children abstract concepts like scale, identity and rotation through physical engagement with the world. Humans literally use objects to think with. The theory of distributed cognition suggests that these scaffoldings are an essential part of complex cognitive structures often thought of as abstract, such as mathematics, language etc. So archaeology's embodied material base works well with the architecture of the human mind.

There was a compass beside the shape sorter. It was a poignant reminder that this physical relationship with humanity has not always been appreciated. Archaeologists want abstract concepts to climb the semiotics hierarchy from mere index to powerful symbol. Indexical signifiers are at the base with little cultural elaboration. Abstraction leads to icons and ultimately to symbols. But the index is as culturally expressive as the symbol. The compass is an index since it responds directly to the world. But it is still culturally constructed. First the compass itself is created, then the scale is calibrated, and then experiential sense of place is given to different values. Of course, the compass became a symbol as well - of Cartesian geometry and its effects on contemporary sense of place.

The importance of place in archaeology had grown immensely since the late 1960's. This was more than the development of landscape archaeology. Places were now considered important for their own narratives and not just for where they sat in the 'human story'. Similarly different regions of the world were recognised to have their own pasts rather than all archaeology being grist to a totalising mill. These understandings of place complemented an increasing interest in the way spatial behaviour reflects and forms social relations.

Place and movement! There was more than one alcove in this tomb and she needed context to make her decision. It was only a few steps to the south alcove where she was expecting more surprises. So she was disappointed to find nothing new lying there. Then it dawned on her. The tomb was acting as a memory palace and the empty alcove was a niche for a new idea to complement these things she had been mulling over for years.

The idea behind the memory palace is that things in places recall abstract notions and emotions. The memory palace is mnemonic system used largely by orators. Cicero is a famous early proponent, but it continued to be relied upon well into the Renaissance. It works by memorising a real place; the more structured the better, hence the term palace. Objects representing different aspects of the speech are deposited within the palace. When recall is necessary the orator moves through the place in thought and encounters the objects, which call the memories.

She had often used the system before; first for speaking without notes, then for incubating arguments. An idea held in this way is more fluid and it allows the argument to deepen before it becomes fixed in its final form - different paths through the place can be taken, objects can be moved, added to, replaced. So many archaeologists do this, without considering its early roots. The use of artefacts and context is a common structure in archaeological argument. Excavation and survey reports are often spatially structured. The illustrated lecture is often an indoor version of a site tour or a field trip with the advantage of avoiding the bus journey.

Memory's power lies in its fluidity. In addition to allowing fluidity for individual practitioners this structure evokes memory strongly but allows the composition of that memory to respond to the individual journey. Each place can also hold more than one object indeed a single palace can be used to hold many different arguments - or other less polemic memories. Indeed, the more often a place is put to work the better it holds memories and the more complex the relations between them.

This was one of the real values behind the multiplication, even fragmentation of methodology within archaeology. Scientific approaches, such as paleoecology, aDnA or stable isotope studies, had become well established. But they were rarely even discussed at the same conferences as research on social relations. Recently there had been attempts to integrate the two. Now she felt that this desire was a continuation of the unified theory drive she remembered from her undergraduate days. While some research can integrate many approaches, independent analysis is still useful. Each consideration of a place produces a richer past. Even if people don't understand or use pollen analysis, it produces another set of objects in a memory palace.

Aha!' she thought 'This is why I felt coming here would help. I've thought through so many problems here, or using this place as my frame for thought. It holds my earlier decisions. But couldn't a shopping mall do the same thing?' She felt her excitement deflate. 'No.' She fought against her own cynicism. 'More than a well structured space, this is a place. It holds more than just my past. The decisions and lives of people stretching back to the Mesolithic have shaped my experience of this tomb. Memory is not only personal and internal. It forms part of shared experience and is constructed and reconstructed through deliberate acts.' She left a key ring from Tokapi Palace in Istanbul. The more vivid the symbol the more robust the memory and she didn't want to forget this train of thought.

She felt more confident as she moved to the western alcove. It was deepest, most elaborate. Surely it would crystallise these old thoughts and new ideas into a plan she could live with.

But it contained only two objects, a mattock and a small sculpture of a dragon woven from beads. It made her heart ache to consider the pair and the chasm in archaeology that they represented for her. The gulf lay between academic and private sector, between field and theory, between doing and knowing - the ultimate enlightenment duality emphasised as the enlightenment was castigated for its dualisms. It was this gulf she had been attempting to bridge. But in reality she could barely straddle it and the pain was making her consider leaving archaeology altogether.

Although she had used a mattock uncountable times, in research excavation as well as private sector archaeology, it always reminded her of the experience of whacking through a particular clay and cobble surface and feeling the softer ditch fill beneath. It was a body memory and the interpretation of bank, surface, ditch were embodied interpretations.

Much of the scaffolding of recording systems is there to translate this body knowledge into rational structures. Sadly, many of the intended audience long for experience rich accounts, which are carefully excised from field records. Similarly, much academic writing tries to communicate rational thought processes in experiential fashion - when readers outside of academia often want to map abstract thought onto their own experience.

This is why the woven sculpture called the chasm for her. It was interesting, and non-linear, and even beautiful - but it was complete. She had created it and it stood on its own. Yes, it was an advance on the single strand necklaces she had made as a child, but it had no connecting points. All her thoughts about renaissance memory palaces felt like the same kind of introspective indulgence. She had come to understand her joy in the pursuit but couldn't justify drawing a salary for it.

But, turning to leave, her eye was caught by a small gold pin. Picking it up, she saw a figure of a woman in long robes. It called to mind a rough and rocky mountain robed in cold mist. A souvenir of Knock, an Irish pilgrimage site. Pilgrims use things to remind them of place, and places to remind them of ideas, and ideals. Pilgrimage is a re-embodiment of the abstraction of a memory palace. Landscape has long been recognised as a 'vast mnemonic system'. Archaeology, using 'things in place' as its core data set is uniquely well placed to enrich people's memories. Each story, description, explanation or argument from whatever faction enriches the potential memories associated with a place and allows people to create more complex memory palaces.

In learning and in teaching fieldtrips had always been her most transformative exercises. This was also how non-archaeologists she knew appreciated archaeology. Either as tourists, connecting their experience to particular places, or by reading about particular sites and the arguments archaeologists were having about them. People often asked her what was new at a particular site. Only her mother asked after the current opinion on the formation of the state.

She had been brought full circle to her own need for the past as a human characteristic. She needed the past to create herself and explain the world. A memory palace was structured response to that need. What archaeology offered was a broader range of objects/concepts than her own life supplied. The multiplication of archaeological techniques and interpretation made for constant surprises. The subversive experience was discovery, which reveals the unexpected and so turns the world upside down. The pleasant shock of finding that being human doesn't mean being 'just like us'.

Granted, a lot of interpretation in the 'heritage industry' hammers out the novel and makes the past seem like a cosier version of the present. But that was only one window. The growth of archaeology was part of proliferation of vistas on the past. Archaeologists creating and curating multiple overlapping memory palaces empower other people to construct their own pasts. "Which is a good enough reason for people to pay my salary", she thought.

She stepped from the tomb renewed. She felt the benefit of the move away from unified theory. The gaps between archaeologists provide handholds for everyone else. She had found which group she belonged to within archaeology. There were plenty of other people concerned with diverse receptions of archaeology. She felt no need to predict or dictate the path that other archaeologists would take. She wouldn't proceed by interpreting for 'a public' but by encouraging people to build their own memory palaces with the finished and solid objects she created.

Archaeology once again held excitement and challenge and intellectual reward. What's more, it had a deeper value than tourist dollars. People use the arguments, stories, descriptions, drawings, and maps that archaeologists create to build pasts that work for them. The joy, and the pain, in the endeavour make it relevant to others. She raised her eyes to the fields that had been the focus of her earliest research.

The fresh harrow-lines seemed to stretch like the channellings in a new piece of corduroy, lending a meanly utilitarian air to the expanse, taking away its gradation, and depriving of all history beyond that of the few recent months, though to every clod and stone there really attached associations enough to spare - echoes of songs from ancient harvest-days, of spoken words, and of sturdy deeds. Every inch of ground had been the site, first or last, of energy, gaiety, horseplay, bickerings, weariness (Hardy 1929, 53).

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements I would like to thank Kathryn Denning, Cornelius Holtorf and Eileen Reilly for their useful comments on earlier drafts of this paper.

Bibliography

Bibliography

(organised according to position and to object reference in the text)

The approach

LeGuin, U. K. 1969 [1998] The Left Hand of Darkness. London: Orbit

Andrews, G. Barrett, J. C. and Lewis, J. S. C. 2000 Interpretation not record: the practice of archaeology. Antiquity 74: 525-530.

Entrance

Jack in the Box

Neustupnı, E. 1971 Whither Archaeology. Antiquity 45: 34-39.

Isaac, G. 1971 Whither Archaeology. 45: 123-129.

Shanks, M. & Tilley, C. 1987. Social Theory and Archaeology. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Richards, M.P. and Hedges, R.E.M. 1999 A Neolithic revolution? New evidence of diet in the British Neolithic. Antiquity 73: 891-897.

Strassburg, J. 1997 Inter the Mesolithic - Unearth Social Histories: Vexing Androcentric Sexing through Stroby Egede. Current Swedish Archaeology 5:155-178.

Eastern Alcove

Willow pattern sherd

Nanoglou, S. 2001 Social and monumental space in Neolithic Thessaly, Greece European Journal of Archaeology 4:303-324.

Brown, K. S. 1998 Contests of heritage and the politics of preservation in the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. In: Meskell, L. (ed.). Archaeology Under Fire: Nationalism, politics and heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. London: Routledge, 68-86.

Shape Sorter

Clark, A.1997 Being There: Putting Brain, Body, and World Together Again. Bradford: MIT Press.

Compass

O'Neill, L. 1993 Peirce and the nature of evidence. Transaction of the Charles S. Peirce Society 29: 211-223.

Ndoro, W. and Pwiti, G. 2001 Heritage management in southern Africa: Local, national and international discourse. Public Archaeology 2: 21-34.

South Alcove

Empty alcove/Key-ring from Tokapi palace

Yates, F. 1966 The Art of memory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Chapman, H. P. and Geary, B. R. 2000 Palecology and the perception of prehistoric landscapes: some comments on visual approaches to phenomenology. Antiquity 74: 316-319.

Samuels, R. 1994 Theatres of memory. Volume 1: Past and Present in Contemporary Culture. London: Verso.

West Alcove

Mattock

Hodder, I (ed). 2000 Towards Reflexive Method in Archaeology: The Example at Çatalhöyük. McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research / British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara Monograph No.28.

Woven bead sculpture

Jones, A. 1999 World on a plate: ceramics, food technology and cosmology in Neolithic Orkney. World Archaeology 31: 55-77.

Souvenir of Knock

Lynch, K. 1960 The image of the city. Boston: MIT press.

Holtorf, C. 2001 Fieldtrip theory: towards archaeological ways of seeing. In: Rainbird, P. and Hamilakis, Y. (eds.). Interrogating Pedagogies. Archaeology in Higher Education. British Archaeological Reports, International Series 948. Oxford: Archaeopress, 81-87.

Meskell, L. 1998 Archaeology Matters. In: Meskell, L. (ed.). Archaeology Under Fire: Nationalism, politics and heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. London: Routledge, 1-12.

Return to the world

Hardy, T. 1929 [1969] Jude the Obscure. London: Penguin.

Sarah Cross May (biography)

A key strand in Sarah's professional life has been GIS and recording

systems, this may be due to the complex path her own life has taken.

Tacking back and forth across the Atlantic since 1987, her main research

interest has been Irish Prehistory and archaeological theory. Most of

her publications on these topics are under her maiden name, Sarah Cross.

Her interest in how people use the past and why the work is significant

has led her increasingly to research on contemporary archaeology

including zoos and murder sites. She is now a Senior Archaeologist with

English Heritage and can be contacted at

[email protected]

|