England's Historic Seascapes: Scarborough to Hartlepool

Cornwall Council, 2007. https://doi.org/10.5284/1000201. How to cite using this DOI

Data copyright © Historic England unless otherwise stated

This work is licensed under the ADS Terms of Use and Access.

Primary contact

Charlie

Johns

Cornwall Council

Kennall Building, Old County Hall

Station Road

Truro

TR1 3AY

UK

Tel: 01872 322056

Resource identifiers

- ADS Collection: 744

- ALSF Project Number: 4731

- DOI:https://doi.org/10.5284/1000201

- How to cite using this DOI

Introduction | Seascapes Character Types

Foreshore

- Introduction: defining/distinguishing attributes and principal locations

- Historical processes; components, features and variability

- Values and perceptions

- Research, amenity and education

- Condition & forces for change

- Rarity and vulnerability

- Sources

Introduction: defining/distinguishing attributes and principal locations

The Type Foreshore includes the following sub-types:

- Sandy foreshore;

- Rocky foreshore.

Components of this Type include:

- kelp and kelp harvesting areas;

- shellfish and bait gathering areas;

- industrial extractive remains (rutways, ironstone and jet mines);

- sewage outfalls and pipelines;

- sea defences (groynes, breakwaters);

- military defence structures (anti-tank cubes, batteries, minefields, pillboxes, trenches and weapons pits);

- landing places (quays, jetties, access tracks for carts);

- potential buried palaeo-landscapes;

- fossils;

- recreational fishing areas.

Historical processes; components, features and variability

Foreshore comprises the sandy, silty or rocky areas running from low-water mark to the cliff and can contain important archaeological remains either at its surface (eg quays, breakwaters, industrial workings) or buried beneath it (eg old land surfaces, overwhelmed quays).

What are now often desolate foreshores were once thronged by seaweed gatherers, bait gatherers (known as 'flither pickers'), coal ships being unloaded (Figure 9.52), jet miners, ironstone miners and fossil collectors. There would have also been numerous fishermen drying their nets, the poorer people gathering driftwood for fires and sandstone for scrubbing floors, and the children picking up coal spilt on the beaches where colliers berthed (White 2004, 122). Bait digging occurs mainly during the winter months (September to March), while collection of bait from rocky shores is mainly done during summer months. Periwinkle picking, both for local consumption and export, also takes place on rocky shores throughout the year. Collection of lobster and crabs is mainly carried out in the summer months.

Figure 9.52. Coal being unloaded from the Diamond of Scarbrough, Sandsend beach (© Whitby Museum)

Common rights to bait, crabs, and lobsters still exist and local Acts apply to people collecting a variety of materials. There is no single body that regulates these activities, and management is usually achieved through voluntary agreements and codes of conduct which are promoted through local or national representatives (DTI. 2002, 31).

Most human activities which have left remains in this Type are connected with maritime affairs but there will also be prehistoric remains from the Bronze Age or earlier, when land that is now inter-tidal was dry ground. So there will be remains of 'submerged forests' (former soils with plant macro-fossils preserved in them e.g. at Hartlepool (Figure 9.53)) and, potentially at least, the remains left by people who lived and worked in and around these forests. Buried prehistoric land surfaces will contain palaeo-environmental evidence (e.g. macro- and micro-fossils, pollen), as well as human artefacts. Palaeo-environmental evidence can relate to an area's vegetational history or to the processes of submergence and coastal or estuarine change.

Figure 9.53. Peatbed and log exposed at Hartlepool beach (© Hartlepool Arts & Museum Service)

Most features, of course, will relate to the use of the coasts and estuaries for fishing, shipping and industry. Some will still be used (e.g. quays, piers) but many will be abandoned or ruined, visible only as low footings of walls or lines of rotting timbers. Piers, jetties, sea-defences and breakwaters are the more substantial of these. Wrecks or hulks of ships and boats survive on rocky headlands. Industrial remains include rutways (Figure 9.54) and partly submerged shafts (and the footings of jetties serving them).

Figure 9.54. Rutways cut into the foreshore at Saltburn

Bait for the long lines was gathered on the foreshore, mainly by wives and children. The preferred bait was mussel, although if these were unobtainable limpets served as an alternative.' [other baits included whelks, 'paps' or a type of large sea anemone, razor-shells, sand worms (lug worms), nereid worms, sand eel and squid occasionally, scallops (or queenies brought up and back by trawlers) (Frank 2002, 98). Also there were large hermit crabs (in Whelk shells) used in the 1950s and 60s called "Telpies" though I don't know how much longer or earlier they were used (David Pybus Pers Com).

Once the men had gone off fishing, wives, sisters and daughters went down onto the bleak, exposed scaurs prising the limpets off the rocks and gathering them in wicker baskets called swills (Frank 2002, 157). Often if bait was exhausted in one area the women would travel great distances, round trips of up to 30-40 miles to acquire bait from other sources, eg Staithes women sometimes travelled all the way to Robin Hood's Bay. Once the bait had been gathered the flithers or mussels had to be skaned, the soft part, the actual bait, removed from the shell. Skaning and the baiting of the hooks themselves was done in the home (Frank 2002, 165-6).

Kelp was also extensively harvested from the foreshores along this coast. From the early 17th century, the word kelp was closely associated with soda and potash (important chemicals in the alum industry) which could be extracted from burning seaweed. The seaweeds used included species from both the orders Laminariales and Fucales. The word kelp also directly refers to these processed ashes. Seaweeds have also been collected for use as fertiliser as they are nutrient-rich and alkaline.

We can perhaps gain an insight into the kind of life lived by the kelpers in along this north-east coast from John Gunn's description of the kelpers in Orkney in 1908, in his book The Orkney Book :

'When the gales sweep up from north or west, tearing from its deep sea-bed the red-ware, of which the long supple stems are known as "tangles". Should the wind freshen to a gale during the night, the diligent kelper is up and out before the first glimmer of dawn. Buffeted by the wind and lashed by the stinging spray, he peers through the darkness, watching for those shadows against the white surf of the breaking waves which he knows to be rolling masses of seaweed and wrack. He is armed with a "pick", an implement resembling a very strong hayfork, but with the prongs set, like those of a rake, at right angles to the handle. With this pick, struggling often mid-thigh deep in the rushing waters, he grapples the tumbling seaweed and drags it up to the beach, out of reach of the waves. For the wind may change, and the "brook", as he calls a drift of weed, if not secured at once, may be carried out to sea again, or even worse, to some other strand where it will be lost to him. Of course, the winds and waves often do this work alone, and pile the tangles in huge, glittering rolls along the beaches'. He concludes, however, that 'on the whole the kelper's lot is not an unhappy one. His work lies in pleasant places, and it is eminently healthy, and his days, as a rule, are long in the land and on the sea'

After being cut, the seaweed was carted up from the shoreline and dried on an area of beach or coastal grassland. It was then burned in large trenches, often stone-lined, for four to eight hours. The men would then beat the weed into a mass using long-handled iron mallets or hooks known as 'kelp irons'. This was covered with stones and turf, to protect it against moisture, and left to cool overnight. The following morning the pieces of kelp ash were broken into lumps and transported by ship to where it was required.

The practice afforded landlords huge incomes and it was so lucrative that in some areas it was not unheard of for all the people of an estate to be set to work on the seaweed, much to the detriment of the land. The alum industry only accounted for 4% of the national kelp trade which was badly affected by the increasingly available chemical industry by-products There was a short period of recovery when a process for extracting iodine from the kelp ash was discovered but this was short-lived. By the mid-20th century, it was confined to a few places in the Outer Hebrides.

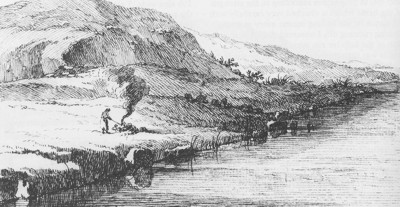

R.R. Angerstein illustrated (Figure 9.55) and wrote of kelp burning at Staithes in his illustrated travel diary (1753-55):

'A great deal of kelp is burnt at Staithes. This is used in precipitation of alum brine. Kelp is burnt from a plant which grows on rocks by the sea, underwater at high tide but easily accessible when the tide is low. The leaves of the plant are thick, bulbous and very large, and the plant is firmly attached to the rock. It is cut, laid on the beach to dry and burnt in a small oven built of loose stones in a circle. The best time to burn kelp is from 15th April to the end of August. Children and old women are also employed in burning fern ash. Having a regard for its high salt content, this could also be used for precipitation of alum boiling, but it would be dearer here than kelp. The reason of the low price of Staithes kelp compared with the Scottish product is that in Scotland they are able to burn the kelp on the rocks. Here at Staithes it must be burnt on the ground where sand and other contaminants get into it'

Figure 9.55. Kelp-burning at Staithes (© Science Museum)

Another component of the foreshore is coastal infrastructure, such as ports, harbours and sea defences. Archaeological remains on the foreshore can be affected by the construction and maintenance of this infrastructure, as well as by the indirect impact of the defences.

The foreshore is also a valued place for recreation activities such as fishing, sunbathing and sea-bathing.

Values and Perceptions

The coast has seen continuous activity since early prehistory, but it has often been viewed from either a purely terrestrial setting or a purely marine environment. Foreshores, however, were regarded as distinct areas, neither land nor marine, with the intertidal area frequently being ignored.

The ruined remains of quays and breakwaters, and the existence of buried land surfaces, will not normally be known about but rotting hulks of wooden boats will be eerie landmarks for many.

The recreational use of the foreshore is highly valued by many, often being associated with holiday time, rest, relaxation and fun. Many also value the foreshore as a place to conduct their hobbies, interests and even their jobs, e.g. dog walking, kite surfing, beachcombing, painting, and writing.

Research, amenity and education

Surveys, such as those carried out by Buglass (2002) at Hole Wyke and New Gut dock, have provided the opportunity to integrate a range of archaeological features to produce a better overall picture of this Type. Hole Wyke, in particular, illustrates the evolution from the use of open beaches in the early years of the alum industry, through jetties and stages, to complex systems of tramways and tunnels (Buglass 2002, 106).

At Hartlepool flints, animal bones, and wooden stakes have been found during fieldwork on the foreshore. Excavations of stratified deposits on the beach at Seaton Carew have uncovered what appears to be a Neolithic or Bronze Age fish trap. Such finds suggest that this is an area of special significance (Fulford et al 1997, 154).

Further archaeological and historical work on the kelp, baiting, and recreation activities should be encouraged.

Condition & forces for change

In Hartlepool Bay patterns of sand movement and accumulation have changed in recent years with the growing extent of the sea defences so that now there are substantial depths of modern beach sand covering the underlying deposits of peat and clay, which formerly were exposed from time to time (Waughman 2005, 142).

There will continue to be gradual erosion by the sea. Human forces for change include the construction of sewerage schemes and coastal defences. As well as the construction itself, the consequent movement and shifting of water and sediments can damage historical and archaeological remains. Treasure-hunting and some forms of fishing can also be very damaging.

Rarity and vulnerability

The foreshore from Scarborough to Saltburn is part of the area designated as a Heritage Coast.

Recommendations

Further palaeo-environmental work should seek to fill significant gaps in the sequences already obtained and there are a number of areas of great potential, for example the 19th century docks at Hartlepool where the initial construction appears not to have destroyed the earlier deposits, also along watercourses and buried channels inland, and beneath former dune systems where prehistoric and Roman deposits may have been sealed by the accumulating sand dunes (Waughman 2005, 142).

The potential existence of buried features along foreshores should be considered when dealing with proposed developments. The good maintenance of extant features should be encouraged and if they are protected statutory constraints should be enforced. More research into this Type is required and good management will be made easier through the production and implementation of integrated management plans. Both natural and historical interests should be fully considered. As well as protecting vulnerable but important remains, these plans should aim to improve the interpretation of this Type and thus increase public enjoyment of it.

Sources

Publications:

Berg T and Berg P (trans) 2001. RR Angerstein's Illustrated Travel Diary, 1753-1755: Industry in England and Wales from a Swedish Perspective. Science Museum

Buglass, J, 2002. The Survey of Coastal Transport in the Alum Industry, in Steeped in History. The Alum Industry of North East Yorkshire

Department of Trade and Industry, August 2002. Human Activities in the SEA 3 Area.

Fulford, N, Champion, T and Long, A (eds), 1997. England's Costal Heritage: a survey for English Heritage and the RCHME. RCHME and English Heritage Report 15

Herring P, 1998. Cornwall's Historic Landscape. Cornwall Archaeological Unit, Truro

Waughman, M, 2005. Archaeology and Environment of Submerged Landscapes in Hartlepool Bay, England, Tees Archaeology Monography Series, 2

White, A, 2004. A History of Whitby. Phillimore, Bodmin

Websites:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kelp