England's Historic Seascapes: Scarborough to Hartlepool

Cornwall Council, 2007. https://doi.org/10.5284/1000201. How to cite using this DOI

Data copyright © Historic England unless otherwise stated

This work is licensed under the ADS Terms of Use and Access.

Primary contact

Charlie

Johns

Cornwall Council

Kennall Building, Old County Hall

Station Road

Truro

TR1 3AY

UK

Tel: 01872 322056

Resource identifiers

- ADS Collection: 744

- ALSF Project Number: 4731

- DOI:https://doi.org/10.5284/1000201

- How to cite using this DOI

Introduction | Seascapes Character Types

Navigation Channel

- Introduction: defining/distinguishing attributes and principal locations

- Historical processes; components, features and variability

- Values and perceptions

- Research, amenity and education

- Condition & forces for change

- Rarity and vulnerability

- Sources

Introduction: defining/distinguishing attributes and principal locations

This Type includes the following sub-types:

- Navigable river channel;

- Dredged channel or area.

This Type is usually found where active management has been undertaken in order to maintain the accessibility of a stretch of water for safe passage. It has close associations with the Types Navigation Area/Route and Navigation Hazards.

Components of this Type include dredged channels, such as the Tees Estuary and entrances to the harbours at Hartlepool and Whitby. Increased trade along the north-east coast, particularly from the 19th century onwards, saw greater volumes and larger vessels seeking access to what had been traditionally hazardous and restricted river and estuary channels. Industrialisation forced port authorities to improve and maintain navigation access by dredging, the spoil often dumped out to sea. Creating channels also involved the reclamation of adjacent land, sand banks and saltmarsh, and the construction of retaining walls (also see Energy Industry).

Navigation channels also take the form of rock cuts, such as 'the Sledway' passage at Whitby. In the ironstone and alum producing areas many smaller cuts, now almost indiscernible on the foreshore, would have allowed vessels to dock and load. Several of these also have remains of piers and/or staithes structures associated with them. Other cuts would have allowed landing places for the small and distinctive fishing craft of North Yorkshire, the 'coble'.

Historical processes; components, features and variability

Navigable river channels are included in this Type as they have long been used for ship, boat or barge transport. Medieval and post-medieval river traffic brought life and busy activity to the banks of rivers, such as the Tees and Esk. Quays and wharves fronted riverside villages with warehouses, industrial furnaces, processing factories etc serving industrial and agricultural hinterlands. From at least the medieval period ferries criss-crossed the rivers, linking banks, A medieval ferry route existed at Hartlepool and a 19th century route is recorded across the Tees, prior to the Transporter Bridge being built.

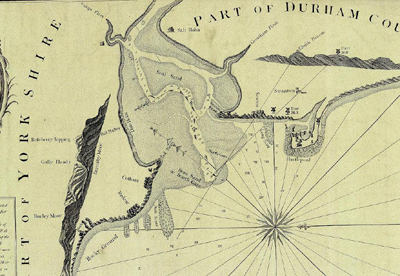

In this Type the River Tees, and in particular the estuary itself, has undergone the most radical dredging, realignment and maintenance (Figure 9.37). Between 1762 and 1853 "the sea had by steady steps advanced upon the Tees Estuary and the Bar was now upwards of a mile westerly" than it had been ... in previous years". It was even something of a misnomer to speak of the main channel to the river because there were at least three different channels, each pursuing an erratic course to the sea: "they were of an erratic nature too, these channels, and given to suddenly picking up their bed and moving to a fresh position without the slightest warning" (Le Guillou 1975, 2).

Figure 9.37. River Tees, Dobson (1802) (© UKHO)

In May 1808 an Act of Parliament created the Tees Navigation Company. In 1828 the Company made the "navigable cut from the east side of the Tees near Portrack into the said river near Newport". It was about 1100 yards (1005m) long, 250 yards (228m) wide and 16 feet (4.9m) deep and shortened the journey to the sea by three quarters of a mile (1.2km) (Le Guillou 1975, 17).

In the mid-1820s the Tees Navigation Company extended its dredging activities; forced by developments which had resulted in the opening of the Stockton to Darlington Railway and the gradual growth in coal shipments from the Railway Company's staithes at Stockton. Ships of only 150 tons or under could be handled at those staithes - "if of a larger class, they had to be laden up at the 9th buoy by means of the keels" - largely because of the number of shoals in the river, one of the most formidable of which was at an island called "Jenny Mill", a little distance above Blue House, "where it was not uncommon to see 5 or 6 ships laying from not having water over the shoal." An old dredger was acquired by the Tees Navigation Company and, slowly, the shoal at Jenny Mill, was removed altogether, as was a major one at Newport (Le Guillou 1975, 15).

Middlesbrough Dock was officially opened for business in 1842.' It has an area of 9 acres of water service and is entered by a channel rather more than a quarter of a mile in length. There is a capacity for 150 sailing vessels of large size and in moderate spring tides there is 25 feet of water in the dock and 19 in the channel' (Le Guillou 1975, 24).

'30th June 1852, "An Act for the Conservancy, Improvement and Regulation of the River Tees, the Construction of a Dock at Stockton, the Dissolution of the Tees Navigation Company, and other Purposes" received Royal Assent. This Act was probably the most important single decision affecting the fate of the river Tees - at least until 1967' (Le Guillou 1975, 30). 'By the Act, the Commissioners were granted a number of powers -[they could] cleanse, scour, cut, dig, open, deepen, straighten, and otherwise improve any part, thereof, and the Banks, Shores, Cuts, Canals, Channels, Streams, Water Courses, havens, Creeks, Bays, Inlets, and other Parts thereof, so far as the Tide flows and reflows and may remove and destroy any Rocks, Shoals, Shallows, Mud and Sand Banks and other obstructions therein - and may construct, alter, and repair any Jetties, Dams, Mounds, Groins, Embankments, and other Works, Machinery, Apparatus, and Conveniences, and may do all such things as the Commissioners from time to time think necessary and expedient for any of the Purposes of this Act...'.

In 1852, there were three or four channels along which the Tees flowed from Middlesbrough to the sea, not one of which was satisfactory from the point of view of navigation. A number of reports on the river arising from surveys carried out by the Admiralty engineers, all pointed out that the river would tend to clear itself by scouring if it was properly channelled. The Tees Commissioners closed all but the South Channel by sheet-piling backed up with slag. The remaining channel was "defined" by the gradual construction of retaining walls, beginning with those at Billingham and over a period of 18 or 19 years over 20 miles (32km) of "Tidal Walls" were constructed, made of 1,356,000 tons of slag material (waste material from the nearby ironstone blast furnaces) (Le Guillou 1975, 41).

Dredgeing is another common feature of Navigation Channels (Figure 9.38). The River Tees has been constantly dredged since 1853 when the first 'Bag and Spoon' dredgers came into operation, with 705352 tons of material being dredged between 1854-77. The object of all this dredging was to 'secure a depth of fourteen feet (4.3m) at low water from the sea up to Middlesbrough, and 12 feet (3.6m) from Middlesbrough to Stockton' (Le Guillou 1975, 38-39).

Figure 9.38. Dredging taking place at Whitby Harbour

At Whitby in the 1850s there were constant complaints about the silted state of the harbour, and until it was dredged in the 1870s, it seems that a vessel carrying any more than 60 tonnes of cargo had difficulty sailing from the port (Owen, 1986).

The long stretch of coastline from Scarborough to the Tees consists almost entirely of cliffs with only a few breaks that offered scope for landings where fishing boats could be drawn up the beach. The major exceptions are Scarborough, Whitby & Tees Mouth. Minor ones are Staithes and Port Mulgrave (Lewis 1991, 156).

Along the Yorkshire coast there are many place-names with references to 'wyke'. A wyke is a place on the shoreline where a boat can be landed and there is a way up from the beach. Examples include Sandsend Wyke, north of Whitby. These sites may offer further potential for archaeological features.

Values and Perceptions

Navigation channels and dredged areas are an important part of any working port or harbour. Dredging craft can often be found moored ready for service and many are shared between coastal communities. For mariners the importance of maintaining a safe draught is imperative to their livelihoods and safety.

Research, amenity and education

The history of navigation channels and dredging is an important aspect of the history of navigation generally. Many former navigable river channels are now lost, buried beneath industrial development, such as in the Tees Estuary. They may offer potential for associated features if buried securely in context, such as wrecked craft, wharves, pilings, jetties, artefacts and even palaeo-environmental evidence. A Neolithic stone axehead was dredged from the River Tees in 1892, about a mile from the mouth (NMR: 27762).

There is limited use for amenity usually because the channels are actively worked, nevertheless small boats, anglers and similar will make use of the water.

The educational potential of this Type is considerable. The River Tees in particular would not have become the industrial port it is unless dredging in the 19th century allowed vessels to navigate up its further reaches. History has shown that as dredging cleared the river and estuary for navigation so the focus of trade and industry moved gradually downstream, from early centres like Yarm and Stockton to Middlesbrough today.

Condition & forces for change

Dredging will obviously have impacted on the archaeological potential of the Tees and Whitby (Esk) rivers in particular. Prehistoric finds have been revealed by dredging activity but it is likely that far more has been lost than recovered. Today many of the dredged channels will have minimal archaeological potential in themselves although the dumped spoil taken from them may have redeposited potential. The dredging effort has not been consistent or very vigorous at Whitby, however, and there is a high probability that the historical river banks are still preserved under subsequent structures (Pybus Pers Com). The dumped material may also smother artefacts, wrecks or palaeo-landscapes making any further investigation virtually impossible, emphasising the need to use area-based studies like this HSC when licensing designated dumping grounds.

Survival of river channels is generally fairly good even though most components are no longer used or have been developed by industry. Quays and wharves were substantial structures and survive well and are still the foci of activities, even when no longer used. They are open spaces towards which roads, streets and lanes run. Bollards, warehouses, lime- kilns, etc, often also survive and are clearly related to them.

The dumping of most forms of industrial waste at sea has been prohibited since 1994. The bulk of the material eligible for sea disposal now comes from port and navigation channel operations, as well as coastal engineering projects. Dumping of dredged materials can, nevertheless, introduce contaminants to the marine environment (DTI 2002). Whitby dredging is unlikely to introduce contaminant to the marine environment as there is no industry producing contaminated sediments needing dredging therefore only delaying the transport of the material to the marine environment. The Tees is different as the sediments there contain many industrial contaminants and even display the chronological history of the industrial development of the upper tees valleys since roman times (Pybus Pers Com).

Rarity and vulnerability

This is an important Type as it has a wide variety of well-preserved components from the early modern period onwards. In those areas that are continually dredged today there is little archaeological potential however there may be remnants of historic dredging activity in some places, eg Whitby.

Recommendations

Navigation channels and dredged areas usually have a negative impact on existing archaeological remains although any material is likely to have been lost very early in the dredging activity, given its history in this area.

The archaeological potential and secondary impacts of dredging and dumping need to be assessed prior and during any further works.

Many features, cuts, rutways, coble landings and 'wykes', etc, exist along the North Yorkshire part of the coast and would benefit from detailed survey and recording.

Sources

Publications:

English Heritage. National Monument Record, Sites and Monuments Record.

Department of Trade and Industry, 2002. Strategic Environmental Assessment Area 3.

Le Guillou, 1975. The History of the River Tees, 1000-1975.

Lewis, M J T, 1991. Ports & Harbours, in D B Lewis (ed) 1991, The Yorkshire Coast. Normandy Press, Beverley, 156-165

Owen, JS, 1986. Cleveland Ironstone Mining.