Kay Hartley Mortarium Archive Project

Kay F. Hartley, Ruth Leary, Yvonne Boutwood, 2022. (updated 2025) https://doi.org/10.5284/1090785. How to cite using this DOI

Data copyright © Kay F. Hartley, Ruth Leary, Yvonne Boutwood unless otherwise stated

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Primary contact

Kay Hartley Mortarium Project

Resource identifiers

- ADS Collection: 4227

- DOI:https://doi.org/10.5284/1090785

- How to cite using this DOI

Industry: MH

Potters | Region/Industry Overview

Introduction to the Mancetter-Hartshill potteries, Warwickshire, with special reference to their most important product, the mortarium

K.F. Hartley

NB. In order to consistently distinguish between the two major military features in the Parish of Mancetter, Warks., I have referred to the early vexillation fortress as being in Mancetter village and have followed Rivet & Smith (1979, 412) in describing the fourth-century defended enclosure on Watling Street (currently described as a 'Burgus') as being in Mancetter, Witherley.

Extent of production

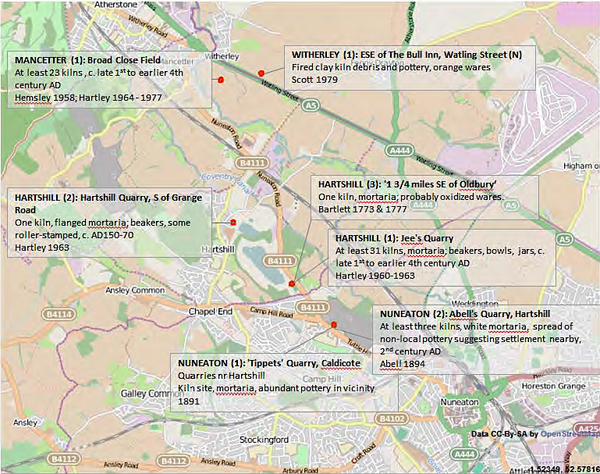

The Mancetter-Hartshill potteries are always described as being in Warwickshire, and in the West Midlands, but their exact limits are unknown and there has been a complete lack of exploration on the Leicestershire side of Watling Street, though Oswald & Gathercole mention much pottery east of Manduessedum and in Witherley (1958, 39).

Pottery is known to have been produced at various points within an area extending in a southerly direction for more than 2 miles, from near to the defensive enclosure on Watling Street, the present A5, which has been identified as the Manduessedum in the Antonine Itinerary (Rivet 1970, p.76; Rivet & Smith 1979, 157-160 & 411-412), and which is now in Mancetter, Witherley, (SP327967). The production extends from some point probably nearer to Atherstone, through Hartshill, including Judkin's Quarry and Jee's Quarry, to Tippet's and Abell's Caldecote Quarries, all north of Nuneaton. The production appears to be within relatively easy access of Watling Street.

The Mancetter and Hartshill areas have quite different geology (Anderson 1971, in Mahany 1971, p21-22). At the Mancetter, Witherley end, knowledge of the extent of pottery production has mostly been limited to finds revealed by the plough, though there have, of course, been accidental surface finds due to other activities. The kilns found in Hartshill were discovered largely as a result of the massive quarrying which has occurred over at least two centuries. The area between the sites, has, as far as I know, never been investigated.

Hartshill

Roman pottery, including stamped mortaria had been found on the site for years by Mrs Doris O. Moreton, her son Peter and Mr Walters a local schoolmaster; the excavations of 1960-61 were organized by the Department of the Environment in advance of the extension of Jee's (later, sometimes called Gee's) Quarry, Nuneaton Road, towards the cricket ground and towards Hartshill. The remains of at least 29 kilns were found (Hartley unpublished; JRS LI, p173 and p195, no. 15 for clay die of Mossius; and, JRS LII, p.168-9, where the term 'Nene valley' is erroneous, it should read 'Oxford'). An extra kiln, excavated in 1963 was cut through by Judkin's Quarry (no.2, 'Hartshill' on above Map) close to the south side of Grange Road, Hartshill (SR328946 approx). There was no opportunity to explore further, but this kiln provides another point to indicate the extent of the overall area of production.

In the late nineteenth century, Professor Windle read 'Notes on a Roman Pottery, near Mancetter' to the Antiquaries of London (Windle 1897), mentioning incidentally, the 'huge quarries' in Hartshill. He listed a kiln found at Tippets quarry c.1891 (finds included a stamp reading SAR·R (Sarrius)). C. Abell worked in a different part of the same quarry and c.1894 a kiln was found there and an almost complete mortarium with a stamp which Windle read as 'VDIO' (this can be identified with confidence as a partially impressed retrograde stamp of Loccius Vibo, Die 1). He continued, that 'in 1897 two other kilns were found in Abell's part of the quarry, one associated with mortaria, the other with iron-rich coarseware (Windle 1897). The first kiln ever published in any way, appears to be one and three-quarter miles south-east of Oldbury, recorded by Benjamin Bartlett in 1791 (Bartlett 1791). In 1983-1984, Warwick Museum undertook the excavation of seven kilns at Cherry Tree Farm (SP 327952), Atherstone Rd, Hartshill, Nuneaton, CV10 0TB (Britannia XV 1984, p295-6). So a total of at least 42 pottery kilns have been located at Hartshill. Considering the size of the quarries at Hartshill, it can reasonably be assumed that these make up a minute fraction of those lost in the quarrying and that many remain to be found. In Scott 1971 and 1975, Keith Scott published his excavations of tile kilns at Griff Hill Farm, and at Chilvers Coton in Arbury Estate. At Weddington, a district in the north of Nuneaton he found what he described as kiln waste and pottery finds (WED 96).

Mancetter, Witherley

In Broad Close Field (NGR SP325969) and neighbouring fields including 'The Furlongs' and 'Three Acre Field', between Watling Street in Mancetter, Witherley and the River Anker in Mancetter village, pottery, baked clay fragments and even kilns, have been revealed when the fields have been ploughed (this is almost certainly true of other fields in the area. One kiln exposed by ploughing in Broad Close Field was excavated in 1958 (Hemsley 1959). As a result of this, The City of Birmingham Museum, in conjunction with the Department of Environment, organized the excavations which took place later and also arranged for a Magnetometer Survey which was undertaken in 1964 by then Dr., Martin J. Aitken, (School of Archaeology, University of Oxford), who had done a similar survey at Hartshill in 1960.

Excavations in 1964-65, 1969-71, 1977 found evidence for a further at least twenty-one kilns, a drying floor, a glass furnace (Vose 1980; Jackson and Paynter, in press), wells, pits, ditches etc., all consistent with it being part of an industrial area. One entrance to a 'practice or marching' camp associated with the pre-Flavian, vexillation fortress in Mancetter village was also found (see below).

Pottery has, of course, continued to be found in the above and adjoining areas. Kiln debris and pottery (no.1 on above Map) was found by Keith Scott at Witherley on the Leicestershire side of Watling Street. Keith Scott also mentions pottery likely to be from a nearby kiln at Holme Close, Nuneaton Road, Mancetter village, (SP323 965), in Britannia XXIX 1998, p397, (c.).

Roman pottery was found by the Revd Don Scholey in the bank of the River Anker (or the River Sence at the confluence of the Sence and the Anker) at Ratcliffe Culey, a village north of Witherley, but its significance is unknown. K Scott found a mortarium of Gratinus at Fieldon Bridge (NGR SP308994) over the R. Anker, 2 km west of Ratcliffe Culey on the Warks/Leics county boundary. He also found pottery on the farm of Mr Simpson, Drayton Grange Farm, Drayton Lane, Fenny Drayton, near Nuneaton, north of Watling St (SP33219671). These sites may not all be linked to production, but some probably will be, and all, would benefit from further investigation.

We now have a total of possibly 64, known kilns in the whole Mancetter-Hartshill area; this is, again, only a minute fraction of the kilns which had existed in this area during a production dating from cAD90-100, until a point in the second half of the fourth century. There was evidence to suggest that some early kilns had been destroyed in antiquity. We had relatively few early kilns and probably a complete absence of kilns dating to the second half of the fourth century though we can be reasonably certain from some mortaria found and others recorded elsewhere, that production did continue though it was probably diminished. It is quite difficult to comprehend that pottery production continued in both areas for more than 250 years. Very marked differences were also apparent, between the two major areas of production known as Hartshill and Mancetter, as well as in different parts of the Parish of Mancetter.

Evidence for other activities in the areas excavated at Hartshill, Mancetter, Witherley and Mancetter village.

There was no evidence of activity other than pottery production in the limited area covered by the excavations at Hartshill in 1960-61. Stokeholes and even kilns were often partially rock-cut; this was also true of the kiln excavated in 1963 in Judkin's Quarry (no. 2 on the map). At Cherry Tree Farm there was no evidence of other activity. We have, for example, no information of where the potters lived. In the Jee's Quarry area there were fragments, many eroded, from up to 16 samian vessels, all in the topsoil or residual in pit-, kiln- or stokehole-fillings. Brenda Dickinson commented that the assemblage, which dates from the late first or early second century to at least the 160s, was very small for the approximately 2 acre area in which it was found.

At Mancetter, Witherley, the situation could not have been more different. We found a working floor, a large drying area, several wells, roads, water channels etc., and also a small glass furnace (Hurst Vose 1980; Jackson and Paynter, in press), all to do with industry: it was a very busy area! We found nothing indicative of living quarters, but all excavations in Manduessedum and along Watling Street show that there was a ribbon development of buildings along Watling Street dating from the mid first to fourth century (see below).

The most important difference from Hartshill is, however, that the excavations in Broad Close Field at Mancetter, Witherley took place between two areas of major importance in the initial military advance.

The vexillation fortress in Mancetter village

Sometime about AD49 the Roman army had reached the midlands and a vexillation fortress was set up in what has become Mancetter village (Scott 1981 and 1998). One feature discovered in Broad Close Field was an entrance to a 'marching' or 'practice' camp which was clearly linked in some way with the vexillation fortress in Mancetter village (Britannia 2 (1971), p263; no finds were associated, except for turf in bottom of the fort ditch). Despite an unexplained remark in Britannia IX (1978), p440, there is no doubt of what this feature was. John Wacher came specifically to look at it when it was open and he was in complete agreement with me about what it was. Aerial survey of the area had revealed more than one of these 'camps'.

Watling Street

This section of Watling Street may have been completed immediately before the troops left Mancetter village. Watling Street was one of the arterial roads of Roman Britain and played a part in the transport of pottery throughout the life of the industry. Oswald & Gathercole (1958) found the remains of what appeared to be an early version of Watling Street and also evidence for a defended enclosure which was considerably earlier than the present one. It would be especially useful to know more about the construction of Watling Street in this area, and, of course, about the earlier enclosure.

A ribbon development developed along both sides of Watling Street, at least from the River Anker (just outside Atherstone) up to the surviving enclosure called Manduessedum and probably beyond that. It consisted of structures ranging in date from c.AD.60-400. Christine Mahany (1971) found that buildings as late as the third or even early fourth-century had been demolished to construct the surviving enclosure. There was also no evidence of buildings within the enclosure which survives; Graham Webster (ibid., p26) discussed this phenomenon along with other similar enclosures along Watling Street. In a Rescue excavation by Douglas Miller, 'a considerable road of heavy gravel, with its surface three times renewed, was also discovered proceeding south-eastwards from Watling Street towards the kilns at Hartshill' (West Midlands Annual Archaeological news sheet No. 6, 1963, unpublished; JRS LIV 1963, p.164; neither plans nor finds seen).

Many of the buildings destroyed may have been linked with the pottery industry either officially or because potters lived there. It is worth noting that many of the mortaria linked with the enclosure and published by Mahany are now realised to be earlier than they were then considered to be, for example, fig 6, no.8 should be dated AD170/180-220; no. 10 is not later than third-century and no.11 would be better dated as second half of third century to early fourth century. Nos. 14, 15 and 17 are probably fourth century. I could not be completely certain that any of those published belonged to the second half of the fourth century.

The Furlongs

The field called 'The Furlongs', adjoins Broad Close Field on the Atherstone side. When it was ploughed in 1996, the fourth century levels of an extensive building with a bath-suite were discovered quite close to Watling Street. This was recorded by Keith Scott and scheduled by the Department of the Environment (Britannia XXIX (1998), p397 (d)). When found, it was thought to be the remains of a mansio, but it has since been described as a villa. Only excavation can provide definitive information, but a mansio on the 'Antonine Iter II', at Manduessedum (Rivet 1970; Rivet and Smith 1979, p.167;) would have had to provide for overnight stays which would include the need for a bath suite; stabling for incoming horses, the provision of fresh horses and presumably oxen for oxen-drawn wagons carrying deliveries. The surviving enclosure on Watling Street, always referred to as Manduessedum, and often, in the past, referred to as the mansio, has no buildings within, which are contemporary with it and we have few details about its possible predecessor (Oswald & Gathercole 1958). It is now considered to be a 'Burgus' (Webster, G).

Finally, with the single exception of 1965, all excavation at Hartshill and Mancetter was done during extreme heat-waves. This was of little import at Hartshill, but at Mancetter, Witherley the natural subsoil was glacial sand and gravel above keuper Marl and it took several days to realise that 'Natural' had to be tested whether it looked like gravel or undisturbed red clay - it was an accepted though not universal practice at both Hartshill and Mancetter to fill in pits, kilns, stokeholes etc which were no longer in use and to seal them with a thick layer of completely fresh, uncontaminated, red clay; they even covered the filled in the large driers in this way. Colin Baddeley's statement on p49, that we completely excavated Broad Close Field is very far from true though it probably looked like that at times (2013). I am certain that many features remain undiscovered in unexplored areas, possibly kilns, but certainly earlier features close to Watling Street which may be of particular interest.

Pottery production in the Mancetter-Hartshill area: When did the 'Production' we associate with this area begin and end;What do we know about it, and its organization, and what is speculation?

Pottery production linked to the vexillation fortress

Comments made by the late Dr.Vivien Swan in her book 'The Pottery Kilns of Roman Britain' (1984, 98-101), about the beginnings of the Mancetter-Hartshill pottery-making industry call for some discussion of the facts we know. As she says Mancetter seems to have been in a virtually aceramic area when the army set up the vexillation fortress in what is now Mancetter village. This is true, we have no evidence of any pottery production in the Mancetter-Hartshill area in the Iron Age and even if it had existed it would not have included the mortarium which had been an introduction from Roman culture even in south-east-England.

Something had to be done to provide supplies for the fortress. Some pottery was imported from the Continent, but there was a common practice during at least the Claudian-Neronian period of the military advance, to have small, local workshops or Depots which served the ceramic needs of the military. The clearest example of these is that at the vexillation fortress at Longthorpe, Cambs, especially since the kilns have been located (Dannell and Wild 1987), but it also happened at Usk, Exeter, Metchley, Newton-on-Trent, Trent Vale and elsewhere. The pottery associated with the fortress in Mancetter village points to there being a similar, small local workshop there (Scott 1981; 1998 (p.33, fig 14f nos.57, 59, 61 and 63 are excellent examples of mortaria probably made locally). Parallels for these mortaria are to be sought in publications such as Dannell and Wild 1987, Hawkes & Hull 1947, and on sites in Germany. The kilns have not been located and could be in the Annexe attached to the fortress. This is the earliest pottery production we know of in the area. Much, if not all of the pottery believed to have been made there, including most if not all of the mortaria, was made with iron-rich clay. The mortaria are red-brown in colour, except for one or two fragmentary bases or bodysherds in a very coarse white fabric which has not been identified.

The samian, glass and coins found during the excavation of the fortress belong to the Claudio-Neronian period. The mortaria present also fit this period, some being imported from the Continent. The only stamped mortarium found has a stamp of Albinus (Die 4), made in the Verulamium region. It is described as from a 'later level' of Pit 3 on Site 1, (Scott 1981, p.9, no. 1). The overall date for Albinus is c.AD55-85. All finds from levels securely linked to the vexillation fortress suggest an occupation within the period AD50-70. It is also very likely indeed that the fort was abandoned cAD71 when the now established Emperor Vespasian sent his new Governor, Petillius Cerialis to pursue the military advance northward.

It is clear that there was some activity in the pre-Flavian period in the area between the Fortress, its Annexe, and Watling Street. In her report on the samian found during excavations in Broad Close Field, Brenda Dickinson states that ' Many of the sherds in this assemblage are not closely datable because of their eroded condition, but it is clear from the better-preserved pieces that samian was in continuous use on the site from the pre-Flavian period to the third century.'

Later pottery finds suggest that some people may have continued to live in the Annexe area after the military left, but the major settlement after they left was probably on Watling Street rather than in Mancetter village.

Earliest mortaria found north of the vexillation Fortress

The early enclosure discovered by Oswald and Gathercole (1958) on Watling Street beneath the surviving fourth-century Burgus did, however, have first-century pottery. I can only comment here about the mortaria and there is not even one sherd found during the excavations in Broad Close Field or published from the 'Burgus', of any mortarium of the type produced for the vexillation fortress (see above). It is perhaps worth noting that those were in red-brown fabric and in the later, intensive mortarium production at Mancetter, Witherley and at Hartshill, it was the norm to use the iron-free clay, first located at Hartshill.

It is almost certainly the use of this excellent clay from the Coal Measures, later known as pipeclay and used to manufacture pipes in later times, which led to the development and continuing importance of these potteries. It was highly exceptional in these potteries to use the iron-rich clay for mortaria; only 2 potters, Coertutinus and INC 52, working in the second century, are known to have ever done so.

In short, there is no evidence whatever, in the mortaria present, to indicate that the small production set up to serve the vexillation fortress, continued and formed the beginning of the extensive pottery industry which continued until some point in the second half of the fourth century. By AD60, if not earlier potters Verulamium region potters like Albinus, Sollus and many others were supplying mortaria over a wide area. The earliest mortaria found in the 'Burgus' and in Broad Close Field are 'imports' from the Verulamium region. These include a counterstamp of Albinus, Die 8A ('F. LVGVDV'), c.AD55-85, found in Broad Close Field in 1970 (1 W70 17 50; and two stamps of Sollus, (Die 1), cAD60-90 one from Broad Close Field in 1977 during the excavations (1 W77 34 19); the second, presumably associated with the earlier enclosure beneath the Burgus (O'Neil 1928, p.184 and Pl.xxvii, no. 2). Christine Mahany published an unstamped sherd (1971, fig. 6, no. 2) which is clearly Flavian. Oswald & Gathercole (1958) published a stamped mortarium of Secundus, AD60-90, of Brockley Hill who is Flavian. At Hartshill, incidentally, there is no record of any mortarium made elsewhere. It would appear that after the abandonment of the vexillation fortress, mortaria were supplied to the area by the potteries in the Verulamium region.

This evidence can reasonably be taken to indicate that in the Watling Street area, including any early activities in Broad Close Field, they were using mortaria made in the Verulamium region before mortarium production began at Hartshill or in Mancetter, Witherley. In the Flavian period the potteries at Brockley Hill, Radlett and elsewhere in the Verulamium region were prospering and their mortaria and some other vessels were being transported widely throughout parts of Britain already conquered. As the Roman army progressed northward, it was commonsense to develop other potteries to shorten transport links and to provide the increased amount needed. The small Claudio-Neronian productions like that linked to Mancetter village were short-term measures.

The beginning of the pottery industry associated with the Mancetter-Hartshill area

On present evidence G. Attius Marinus and Doccas are indeed likely to be the earliest known potters to start producing mortaria at Mancetter, Witherley and Hartshill. The only link we have through potters' stamps, between the Mancetter-Hartshill potteries and earlier mortaria made elsewhere, is in the work of these two potters. Both of these potters were active in the Verulamium region, but interestingly, both were also active earlier still at Colchester (Symonds and Wade 1999, p.199, S21-22 and for DOCAS, S35-36 (ignore S34, it may be wrongly attributed)). The Colchester, Docas die (fig. 4.25, S35 and 36) differs from his common VRW, DOCCAS, Die 1, but the two dies are sufficiently similar and unusual in design to indicate that they are the same potter. These potters are likely to have been in production in the Mancetter-Hartshill area by cAD90/100.

Unfortunately we have only 1-2 mortaria of G. Attius Marinus from the Mancetter-Hartshill excavations, and two Doccas (Die 5) stamps from Oswald & Gathercole's excavation, but there is no doubt about their fabric. We have what is probably a kiln of Vitalis 4 at Hartshill (Kiln 22) and many other stamps of his from both sites; his work mirrors that of G. Attius Marinus so closely that one would expect him to have perhaps learnt his craft in Marinus's workshop. We do not know whether other early potters like Moc, Surus and Septuminus were, similarly former 'apprentices', but it is possible, because G. Attius Marinus was certainly the most important of the early potters working at Mancetter-Hartshill. In addition he appears to have had a stake-out in the Pottery at Little Chester (along with other early Man-H potters), and it is certain that he was also involved in at least one other, still unlocated production. If a number of run of the mill VRW potters had gone with them to Hartshill and Mancetter we might expect to find the unusual VRW practice of keying the extra clay to form spouts, to be present among the Man-Hart potters, but it does not occur.

Potters and Stamps

From the beginning of the Mancetter-Hartshill potteries cAD90/100 up to AD175/180 there was a practice of stamping all the mortaria made. We have records from the excavations at Mancetter, Witherley and Hartshill, of the stamps of at least 44 potters with fairly legible names, 26 with incomplete or uncertain names, one trademark and one herringbone stamp. There are 9 other stamps on mortaria in Mancetter-Hartshill fabric whose stamps were not found at Mancetter or Hartshill, but which have been recorded from Alcester, Warwickshire, and elsewhere, and there will be others.

It was clearly the practice for all the stamped mortaria made in these potteries in the period AD90/100-170/180, to have, basically, two stamps on the flange, one impressed on each side, in complementary positions to the spout. G. Attius Marinus continued to use a 'FECIT' counterstamp just as he had done at Colchester and in the Verulamium region. It was the practice with all other potters in the Mancetter-Hartshill potteries, to make a second, counterstamp impression of their namestamp, trademark or herringbone stamp to the other side of the spout. These stamps, like those in other potteries, can usually be identified, even when, as often happens, the impression is partial or even fragmentary. This makes it possible to record the distribution of mortaria stamped by individual potters. Some potters used only one die-type, but many used a number of die-types throughout their working life. The fact that it is possible to identify not only stamps, but the individual dies used, also makes it possible to identify the distribution of mortaria stamped with individual dies.

Identification of the fabric or fabrics used in different areas of production (i.e. the Verulamium region, the Mancetter-Hartshill potteries, Lincoln, Colchester, Rossington Bridge/Cantley, Corbridge etc. etc.), in conjunction with the identification of potters, and of stamps from individual dies, has revealed that some potters (eg. Sarrius, G. Attius Marinus, Doccas, Nanieco etc), were involved in production in more than one area, either consecutively or simultaneously. The information resulting from being able to identify all these details is of potential, archaeological importance, on several levels, ie. trying to understand how various pottery productions were organized; what was the status of different potters etc. (see Conclusions).

However it came about, G. Attius Marinus and Sarrius stand out as potters involved in production in several areas. We know from the fabrics and dies used that G. Attius Marinus was active not only at Colchester, Radlett, Herts., possibly Brockley Hill, Mddx, and Mancetter-Hartshill, probably at Little Chester and also, at one, if not more, unknown locations. Nanieco was, surprizingly, involved at Wilderspool, making sub-raetian mortaria (Hartley 2012, 5.3, p91 and Hartley and Webster 1973, fig 8, G, and p.93). But it was Sarrius, probably the potter with more Mancetter-Hartshill mortaria recorded than any other, who became involved in workshops at Rossington Bridge/Cantley, near Doncaster (Buckland, Hartley and Rigby 2001, 39-48), and at Bearsden (Breeze 2016, 136-140) on the Antonine Wall. The dies used at these two centres were replicas of his Mancetter-Hartshill Die 4. He was also involved in another workshop, possibly in the north-east at Corbridge, where the die used is not one recorded at his Man-Hart headquarters, but it is likely to be linked with dies in use at Rossington Bridge. These Sarrius productions outside the Mancetter-Hartshill potteries were all relatively small or short-lived in the event, but there is no reason to have foreseen this when they started. There is, however, every reason to believe that his main activity was always at Mancetter-Hartshill. We do not know what his responsibility at the other workshops involved. With G. Attius Marinus, it was the other way round! His period of production at Colchester was minimal and that in the Verulamium region limited, while his maximum production was certainly in the Mancetter-Hartshill potteries.

Extended production in 'pottery hubs'

During the second century and possibly later, it is probable that some small pottery-making hubs were set up, serving forts and nearby settlements where some of the Mancetter-Hartshill potters had a stake-out, sometimes alongside local potters. The workshop at Little Chester was almost certainly one of these, but, they must have transported clay from Mancetter-Hartshill because the clay used there for the mortaria of G. Attius Marinus and the other early MH potters is, with one possible exception (the oxidized fabric of one Septuminus mortarium), not the local one used by the local, Little Chester potters. Also, the way the inclusions are used in some from the Derby Flood Alleviation Scheme, which I have been able to re-examine, differs from the inclusions and how they were used, at both Mancetter-Hartshill and by the local Little Chester potters.

Alcester could have been another such hub, and again the fabric of the mortaria in question, is Man-Hart fabric. There could be other such 'hubs', serving substantial local areas. It may be purely accidental that some apparently Man-Hart potters, like for example Brapuco, have not yet been recorded on the main production sites.

There is evidence to indicate that at least one potter from Mancetter-Hartshill was active in the vicinity of Plas Coch, Wrexham, in north Wales at some time within the late second to early third century (Jones 2011, Archaeologia Cambrensis 160, 51-113). Unfortunately, due to my report not being updated before publication, they appear only as 'variants'. The trituration grit was checked out by the late Dr Geoff Gaunt, but it was after the original report had been submitted. Different areas had been excavated at Plas Coch by two different excavators and the finds were examined by different specialists, so there may be others. In fact the fabric itself is virtually identical to Man-Hart fabric, but the crystalline trituration grit, where it survives, is the real giveaway; it was not possible for me to make a decision on fragments with no trituration grit surviving. There is no question of this trituration grit being used at Mancetter-Hartshill at this period.

The pottery at such centres, and there will be more, need further and very careful study to check out details, including scientific analysis of fabric and especially, study of the trituration grit and inclusions in addition to distribution of stamps belonging to individual dies, etc.

Growth in the manufacture of mortaria and re-organization of the industry

The Mancetter-Hartshill potteries grew in importance during the second century, but there is incontrovertible proof of fundamental reorganization of the industry, beginning perhaps during the decade AD170-80, or before 185. The practice of stamping was discontinued, accompanied by simplifying the formation of the spout. Changes in rim-profile, some, first used on an occasional basis as early as cAD140/150, were developed at the expense of the flanged profiles preferred earlier. Although ordinary coarseware continued to be made, there was growing specialization in the manufacture of mortaria. Until this period, the pottery was fired in kilns of varied type and size and mortaria were probably always fired alongside other wares which needed oxidizing conditions. The practice of firing mortaria in larger, more substantial kilns and perhaps alone, and, to a higher temperature probably began in the late second to early third century (Hartley 1973; Swan 1984). This all indicates concentration on increased production of mortaria, which were fired to a higher temperature.

These changes probably did not occur overnight - mortaria produced after stamping ceased, can be identical in every other way to those made earlier. Then, they remained identical except that, instead of the bead being entirely cut away when the spout was being modelled, it was left almost complete, which involved less work in making the spout. What appear to be the earliest of reeded rims have no more than four, very rounded reeds and, so on. We don't know how long these changes took, but they were very definitely in place by AD208 when we are lucky enough to have a vignette of the new mortaria because Mancetter-Hartshill mortaria made up a significant majority of those surviving at Carpow and Cramond from Septimius Severus's campaigns into Scotland (Birley 1962-3; Dore and Wilkes 1999; Rae & Rae1974 and Holmes 2003). The mortaria associated with Kiln 2 (at Mancetter, Witherley) provide good parallels for many of the mortaria linked with Severus' campaign into Scotland.

The reason for the changes was clearly productivity. It also resulted in much greater uniformity in the product, the kilns and the firing processes. There can be no doubt that, however the changes were managed, the military provided the catalyst behind them. These potteries had their period of greatest importance as the major suppliers of mortaria in northern England throughout the third century and possibly up to the mid-fourth-century. There was only limited competition from potteries in the lower Nene valley and elsewhere.

During the second century there were many local and regional productions in the north of England, including the linked productions at Wilderspool (Hartley and Webster 1973), Walton-le-Dale (unpublished), Carlisle (Johnson, Croom, Hartley McBride et al. 2012), possibly continuing in Scotland when occupied ( ); Corbridge; the Tyne area; Aldborough, North Yorks. (Hartley, KF in Jones, 1964, p64-67) etc, but by the beginning of the third century they had either gone or were in decline and the Mancetter-Hartshill potteries were supplying the majority of mortaria used and this continued with little competition in most areas in the north throughout the third century and in the fourth century until the potteries at Crambeck in east Yorkshire started to make mortaria on a large scale. At some point, probably in the third century, a production was set up in the Catterick area. Judging from its mortaria, it was set up by potters from Cantley. It was very important locally, but precise contextual evidence would be very helpful in providing the date when it began, especially since there are shortcomings in the dating of Cantley pottery. While the local importance of the Catterick industry is not in doubt, its importance beyond that area is still uncertain.

Decline

From at least the late third century onwards there was a progressive change in policy to replace distant sources like those in Dorset for black-burnished ware and Mancetter-Hartshill for mortaria with local sources in the north. It did of course make perfectly good sense to shorten supply lines. Whatever the reason, the Mancetter-Hartshill industry was dealt a very severe blow when the Crambeck pottery, south-west of Malton in North Yorkshire began to make mortaria on a large scale. They were already important for other coarseware from the late third and early fourth centuries but production of mortaria on a large scale seems to have come later.

At Birdoswald for example, Crambeck mortaria are absent from contexts which are earlier than c.AD350, but they rapidly took over afterwards (Hird, in Wilmott 1997, p. 243-250, Analytical Groups 9-12 contrasting with Groups 13-14, the difference in date being between Phase 4b and Phase 5). Further research is needed to check the date when this happened and to check which areas were affected.

Mancetter-Hartshill could still supply what had always been their major local market, Leicester, and other sites in the midlands, but even there they were in growing competition with the Oxford potteries which produced what appeared to be a better range of other coarseware and they would already have had a good trading network in place.

There were certainly mortaria being made at Mancetter-Hartshill which judging from the profile, one would certainly attribute to the second half of the fourth century, but work needs to be done to show their distribution. Interestingly, at least three Mancetter-Hartshill mortaria of this sort and surely attributable to the second half of the fourth century, are present at Richborough (not published); this could perhaps show an attempt to seek new markets because it is a most unlikely place to find them. Such mortaria were certainly found at Mancetter, Witherley, but we had no kiln which could be linked with them. The easiest and most straightforward way to check on the decline in importance of these potteries would be to make a complete examination of all the mortaria from the 'Manduessedum/Witherley' site and, also, at the Watling Street sites like Wall and Tripontium. The decline in number of Man-Hart mortaria will be matched by an increase in mortaria and other pottery from the Oxford potteries. If the same were done at Leicester the picture might be even clearer.

Potters coming from elsewhere to work in these potteries

The varied types of kiln being used before cAD170/180 suggest that potters may have come from different areas. In two instances, however, we have perfect proof of the source of potters who did not stamp their products.

There is one kiln with clearly associated pottery at Hartshill (H61 6), which provides an intriguing sidelight on fourth-century production in these potteries (Bird and Young 1981, 305-7, Appendix by Hartley, K, p.310-311). This was a unique kiln at these potteries (Hartley 1973, fig. 2, G), as was also all the fine-ware type pottery associated with it. Both kiln and pottery showed beyond shadow of doubt that at least one potter had come or been seconded, for whatever reason, from the very successful potteries in the Oxford area, to work in the Mancetter-Hartshill potteries. There were only seven sherds from normal, probably third-century, but residual, Mancetter-Hartshill mortaria associated with this kiln. We do, however, know that Oxford-type mortaria were also being made in these potteries because of a casual find on the site of a perfect Oxford Form M17 in Mancetter-Hartshill fabric with Mancetter-Hartshill trituration grit (unpublished). Young dates the Hartshill 1961 kiln 6 and its pottery to the second quarter of the fourth-century, AD 325-350. Why this move occurred is enigmatic, but it is discussed by Bird and Young.

This is not the only example where one can identify unstamped forms with the area from which the makers came. At Hartshill we had some wall-sided mortaria related to Hull 1963, CAM type 501. There is an Mancetter-Hartshill mortarium of this type at Cramond (Hartley in Holmes 2003, Illus 50, no.15), of the right date to be in Severus' Scottish Campaign, AD 208-211. The maker would have gone to the Man-Hart potteries from either Colchester or elsewhere in East Anglia. There are several mortaria from Hartshill of the same ilk, but less distinctive.

Conclusions

These potteries were at least as important as the Verulamium region potteries, perhaps more so. Both industries were closely linked with the military advance northward. The Oxford production was much more concerned with the settled south.

Even the limited study which it has been possible to make here, of the potters, pottery and even the kilns in all these potteries, raises fascinating questions concerning the pottery industry and its management; the movement of potters etc. Only further study can help in elucidating these.

Perhaps the most interesting of the small finds were two broken, clay dies, one of Mossius (JRS LI, p195, no. 15) and one of INC 52 (Britannia IV, 333, no. 36). No stamps are known from the die represented by the Mossius die and the die of INC52 has an imperfect, stamping face. Both were found among pottery waste and there is every possibility that they were wasters. Interestingly P G Suggett considered the clay die of Matugenus found at Brockley Hill, Mddlx to be a waster (1955, 'The Moxom Collection', p62, no.7).