Anglo-Saxon Stafford. Archaeological Investigations 1954-2004. Field Reports On-line

Martin Carver, 2010. https://doi.org/10.5284/1000117. How to cite using this DOI

Data copyright © Prof Martin Carver unless otherwise stated

This work is licensed under the ADS Terms of Use and Access.

Primary contact

Prof

Martin

Carver

Department of Archaeology

University of York

King's Manor

Exhibition Square

York

YO1 7EP

England

Resource identifiers

- ADS Collection: 912

- DOI:https://doi.org/10.5284/1000117

- How to cite using this DOI

Introduction

In July AD 913 Æthelflæd, Lady of the Mercians, founded Stafford as part of a campaign for the recovery of England from the Danes. She was the commander of the left flank in the northward advance, while her brother Edward the Elder led the pincer movement on the right flank. Wessex had already been won, thanks to the persistence and ingenuity of their father, Alfred the Great.

The primary instrument of this war was the burh, a fortification with provision for residence and trade, which was garrisoned by levy or conscription from its local territory. In Wessex, some record of the procurement system has survived as the Burghal Hidage, which names the places and the human resources required to man them. The places chosen were broadly of three types: former Roman forts or fortified towns, like Winchester, Portchester and Chichester, new foundations that resembled Roman forts, like Wareham, Wallingford and Cricklade, and smaller sites of unknown form at promontories or river junctions, like Lydford and Lyng. Together these places are thought to have formed a defensive system, in which some fortified enclosure was, or was intended to be, in reach of all the people.

Studies of the Wessex burhs have led to the deduction that many of the larger ones were laid out with a street grid, which reinforces the idea that they were intended as towns, as opposed to merely forts, from the moment of their foundation. Surprisingly, this picture has received little archaeological endorsement since it was advanced in 1971: several decades of intensive excavation have strengthened the conviction that in most cases it took another century or so for the more conventional trappings of town life - craft, trade and suburbs - to arrive.

In the Midlands, the Anglo-Saxon towns have been less intensively investigated, but the expectation is that they will be similar in purpose and design to those of Wessex. However, the two military campaigns in south and north were consecutive and there was a difference in their context; while the first in Wessex was defensive, the second north of the Thames, was largely aggressive.

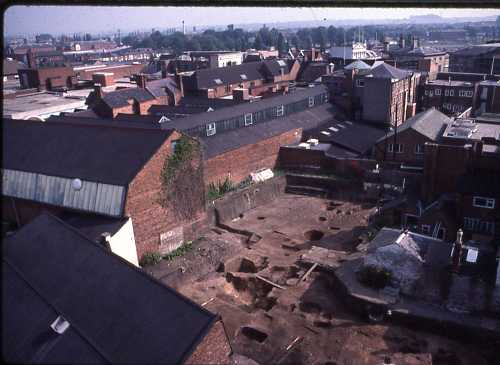

Chance, aided by design, has allowed the emergence of the otherwise not-very-famous site of Stafford as the Mercian town that has seen the most intensive campaign of archaeological research to date. The first investigation there was carried out by Adrian Oswald in 1954 at the site of St Bertelin's Chapel in the town centre. Opportunist recording by members of the local archaeological societies then kept the torch burning until the discovery of late Saxon Stafford Ware pottery in 1974. The site of its discovery, at Clarke Street, was excavated in 1975, and a watching brief in 1977 south of Tipping Street brought to light the first Stafford Ware kiln. In 1979, an evaluation of the whole historic core was undertaken, resulting in a map of the Late Saxon settlement and its deposits. In 1980-85, three more area excavations followed, at St Mary's Grove, Bath Street and Tipping Street, north. Before 1985, Stafford had therefore been explored by five area excavations, stretching east-west across the Late Saxon town, as well as some 30 targeted trenches. The project was also noticeable for its design - a campaign of evaluation, followed by the creation of an Urban Archaeological Data Base and a programme of excavation (three open areas) and environmental analysis. This profited from exceptional support from Stafford Town, Staffordshire County and the Department of the Environment.

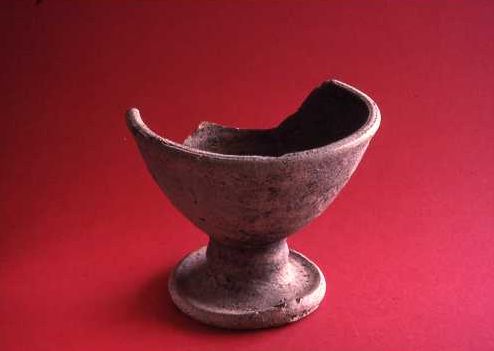

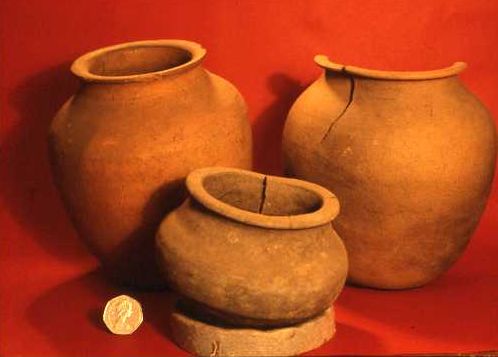

The research campaign of 1975-1985 found that early site of Stafford lay in a peninsula formed by a loop in the River Sow and surrounded by marshland. The peninsula had been exploited in the Iron Age for storing grain and in the Roman period as arable land with some reclamation of the marsh. A north-south axial road, now Greengate street, is argued to have had a Roman origin, and to have remained a crossing point through the otherwise blank centuries that followed. Although there are few suggestive signals, there was no decisive archaeological evidence for occupation between the Roman period and the early 10th century, at which point there was an explosion of activity. A chapel was constructed in the centre of the peninsula at St Bertelin's, with a central burial in a tree trunk coffin. North of the chapel was a large area dedicated to the processing of grain and the baking of loaves of bread and oatmeal bannocks. To the west was a smithy and stable block. To the east of the main axial road were the potters' workshops, producing a wide range of pots, pitchers, bowls and lamps as well as the ubiquitous Stafford Ware jar. Still further east at the marsh edge was the town dump, with piles of pottery wasters and butchered animal bone.

There was no convincing case for a minster at Stafford before the 10th century, although it is not improbable. The prime function of the 10th century site was the production of provender and pots on a large scale, presumably in support of some group of dependent persons, such as an army. The actual location of the defences remained unconfirmed, although such signs as we have, archaeological, documentary and topographical, converge on a rectangular area in the centre of the peninsula that embraced both the church and the grain yard. The potteries and dumps to the east are outside this area, contained by a triangle of streets leading to the eastern causeway across the marshes.

The thesis that has been woven from these discoveries and their dating is consistent with the documentary record, that Æthelflæd, Lady of Mercians constructed a burh at Stafford in AD913. The archaeological verdict is that the activities of the burh were highly regulated and inspired by an image of Rome. The basic form of settlement is hypothesised to be that of a Roman fort, with a vicus to the east. The processing of grain, the provision of beef and the production of pottery were organised, localised and standardised. The finds of three human skulls with pottery wasters perhaps gives an indication of the degree of regulation. This was a lady that meant business, and the business was winning a war.

Anglo-Stafford has so far yielded evidence for coinage, pottery, butchery and grain processing, but no other crafts and few imports. However the distribution of Stafford-ware pottery suggests that the whole of the peninsula was occupied, and by the time of Domesday Book was recognised as having 156 properties. Insofar as archaeological observation has allowed, the emphasis of the place remained largely administrative and military, with a fort, a church and an industrial vicus, until the Norman Conquest. The conquest here was particularly brutal, and resulted not only in the imposition of a castle, but in the destruction and suppression of every other activity except the intermittent minting of coins for about a hundred years.

Redevelopment began in the late 12th century, maintaining the location of the church, the N-S axial street and routes through the Late Saxon industrial quarter to the east, but in other respects redrawing the town plan. A motte was constructed on the western promontory of the peninsula, possibly overlooking a ford, looking also towards the main site of the main castle of Stafford, at Castle Church, some 2 km from the town. Tenements were laid out over the whole peninsula and crafts flourished in them until the early 14th century, when there was another hiatus, followed in the mid 16th century by another revival. In spite of being designated as the shire town, from ?thelfl?d to Elizabeth I Stafford required successive surges of external investment. Perhaps for this reason, it is at Stafford, a place unenthused by the urban project, that the intentions of the crown are particularly graphic.

A synthesis of these ideas is presented and discussed in

Martin Carver Birth of a Borough. Archaeological Investigations in Stafford 1954-2004 (Boydell and Brewer 2010)

Even though the Stafford campaign ended 25 years ago, and has only now been rescued and brought to press, it was not a haphazard exercise and still invites judgement on its design, method, agenda, results and their interpretation. Every town in England has its own archaeological story to tell, but such stories may breed useful generalities. Those that have new light to offer on the 10th and 11th centuries reflect on a period of English history of particular energy and brilliance.

The results of all these excavations and the assemblages recovered from them, and all the preliminary archaeological studies that were accessible, have been gathered from the original contractors, Birmingham Archaeology, and the curators of the finds, Stoke Potteries Museum, edited by Martin Carver and placed in this online archive hosted by the Archaeological Data Service. The archive is organised into Field Reports (FR) which reflect the way the data was originally recorded and assessed. FR 1 contains the Contents and the History of the Project, FR 2 the Evaluation and Design), FR 3 The re-assessment of the excavations at St Bertelin's Chapel, 1954; FR 4 the excavations at Clarke Street, 1975, FR 5 the excavations at St Mary's Grove 1980-5, FR 6 the excavations at Tipping Street north, 1981-8, FR 7 the excavations at Bath Street, 1982, FR 8 Reports on artefacts, FR 9 Reports on animal and human remains, FR10 Reports on plant remains and pollen and FR 11 an essay on the Stafford hinterland by Lawrence Bowkett.

Since a large team was involved, these reports do not always agree with each other, and the rival opinions are represented. The online archive is therefore itself a definitive resource that will hopefully be useful to future researchers.