Watermead Country Park, Leicestershire

Susan Ripper, 2010. https://doi.org/10.5284/1000126. How to cite using this DOI

Data copyright © University of Leicester Archaeological Services unless otherwise stated

This work is licensed under the ADS Terms of Use and Access.

Primary contact

Susan

Ripper

Project Officer

University of Leicester Archaeological Services

School of Archaeology and Ancient History

University Road

Leicester

LE1 7RH

Resource identifiers

- ADS Collection: 964

- ALSF Project Number: 3380

- DOI:https://doi.org/10.5284/1000126

- How to cite using this DOI

Introduction

Watermead Country Park is a two mile long area of wetland located on the Holocene floodplain of the River Soar, a few miles north of Leicester city centre. The underlying geology of sands and gravel occasioned aggregate quarrying to expose a late Neolithic burnt mound on the banks of a Soar palaeochannel. Within the channel a peat deposit contained both butchered animal bones and human remains. Timber pile posts from a later (Saxon) foot-bridge or jetty were recorded crossing the channel in the same location.

'Burnt mounds' are the collective name given to large accumulations of charcoal and fire-cracked stones, located in marginal wetlands, which form the debris from a water heating process in which heated rocks are plunged into a trough of water to produce boiling water and/or steam. While heating water to cook with would seem a straightforward explanation of the function of these sites, the almost complete absence of associated plant/animal/insect/or even pottery debris suggests the hot water was produced for a different purpose; bathing, textile production, preparation of hides, beer brewing pits etc. being just some of the alternative interpretations.

Figure 1: Reconstruction of the late Neolithic plank lined trough with woven withy walls.

The Watermead burnt mound centred on a well-preserved plank-lined circular trough with woven withy walls (Figure 1); a rare survival of structural evidence from the late Neolithic, including evidence of jointing. While extensive sampling of deposits has indicated an absence of evidence for food processing, structural evidence around one of the hearths and a contemporary ditch suggests complex activities, perhaps involving stages. The timber-lining of a subterranean pit implies investment in the site, suggesting it was built to function on more than one occasion. The radiocarbon dating programme proposes that the site was revisited for perhaps 300 years.

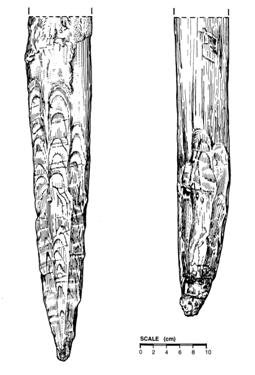

Figure 2: Cut marks on the atlas vertebra of Bronze Age male

The human remains, deposited in marshy ground, included at least two early Neolithic individuals and a late Bronze Age male with cut marks on two vertebrae (Figure 2), indicating that he had had his throat cut. The lack of random damage on all the skeletal material contradicts casual disposal and suggests a persisting attraction to the location. Animal bone from the peat surrounding the human remains included butchered aurochsen, as well as a range of later (Iron Age) species.

Figure 3: Post tips from the Saxon bridge/jetty. Pencil point (left) and buckled tip (right).

The Saxon timber bridge or jetty consisted of only five in situ pile posts (although more were observed by the machine driver) forming a double row of posts. The rows were set 1.5m apart and the upper part of all the posts had rotted off in antiquity. The survival of pencil-like sharpened ends suggests the timbers were not generally driven into the underlying gravels, with the exception of Timber 3, which was clearly compressed and had buckled (Figure 3). No evidence of the superstructure was found, nor any indication of how long the structure was in use.

Animal bone remains both pre- and post-dating the burnt mound site were recovered from the channel silts, many with evidence of butchery. An extensive radiocarbon dating programme has provided both a reliable chronology encompassing all the excavated events and a likely time frame for the burnt mound activity. A complimentary environmental reconstruction has also been constructed, spanning some 10,000 years.

The paper will address current thinking on deposition of human remains in riverine contexts and the dating and use of burnt mounds.