Landscape Archaeology and Community in Devon: An Oral History Approach

David Harvey, 2005. https://doi.org/10.5284/1000091. How to cite using this DOI

Data copyright © Dr David Harvey unless otherwise stated

This work is licensed under the ADS Terms of Use and Access.

Primary contact

Dr

David

Harvey

Department of Geography

University of Exeter

Laver Building

North Park Road

Exeter

EX4 4QE

UK

Tel: 01392 263330

Resource identifiers

- ADS Collection: 406

- DOI:https://doi.org/10.5284/1000091

- How to cite using this DOI

Overview

- Augmenting Scientific Enquiry

- Destabilising 'Official' Narratives

- Offering Alternative Narratives

- The War, Mechanisation, and Landscape Change

- Custodians of the Countryside: Working the Land in Wartime Devon

Augmenting Scientific Enquiry

Oral histories are used within the project not simply as accounts of past history per se but as a source of information which may illuminate and augment other data sources relating to landscape change and help us reconsider the way in which we study the landscape. The aerial photograph below gives two examples of how a contextualised oral history of land use can help us to appreciate certain features which the photograph alone cannot tell us. On the right, the farmer recounts from his personal biography the pre-mechanised method of laying out dung heaps in the field. The narrative on the left refers to how 'leets' (a feature which has been well documented within landscape archaeology) were used to fertilise the fields - telling us much about the reasons why the farm was laid out in this way. In each case, more 'traditional' historical, archaeological and palaeo-environmental techniques would not have uncovered either the detail nor clarity of information to the depth that these oral histories have reached.

Some of those fields were fertilised by streams which came through the farm yard. You had a stream which came through the farm yard which picked up nutrition from the dung heap [...] You had this huge heap of dung and straw and the seepage from that would seep into the stream and the stream would go down and water the meadows, so it was a form of fertilising the meadows [...] you kept it clean near the top of the yard, then it would go through the yard were the cattle would drink and then down to the lower fields...there were those who would tip a load of dung into the stream, just so the water was taking on some nutrients. If you had steep land you took contours on from the steep ground, say every 20 yards down the hill. You'd block the stream and make it run down through that channel and make it soak over the ground and then after a while you'd stop it going along that channel and go down and open up another channel and these channels were opened up every year

The cow dung from the farm yard, you brought it out on the cart, and you dug it out in heaps eight paces apart. Those eight paces meant that when you stood up with a heave-ho or a dung fork you could fling it four yards away from you, you see, so you covered a four yard square from each heap, so you threw some towards the heaps each side of you, and that was the way you dunged your fields.

So the first row of dung heaps were four paces from the hedge and so you could throw it North, East, South and West and then next heap did likewise you see [...] you'd just say 'move on'to the horse and he'd start to walk, then you'd count your eight paces and say 'wow' and dig out the next.

Similarly, techniques such as pollen analysis, while providing a wealth of information on past land uses and environmental change at broad spatial and temporal scales, may fail to highlight small-scale and temporary changes. For example, two farmers in Mid-Devon recalled the planting of a field of gorse (or furze) for two years on previously tilled land during the 1930s. This temporary alteration of land use would have affected the local pollen record. However, scientific pollen analysis would not have been able to explain why such a change had occurred, and may have led to anomalous conclusions about the nature of any such changes in land use, that did not fully appreciate the wider political and social context.

Farming was in a terrible state you see. Landlords couldn't get people to farm the land...they simply couldn't give it away. I remember a field next to our farm being planted with furze. I don't know how ever they got the seeds or whatever to do it, but they did. They planted it and after the first year they clipped the shoots to make it grow out, more bushy like. [Why was that?] For fox cover. Cover to attract the foxes in for shooting. That shows what the land was worth, they preferred to plant furze because the sport was more important. It didn't last long, but they definitely did it

(88 year old farmer, Mid-Devon)

Destabilising 'Official' Narratives

When the Second World War began in September 1939, Britain was faced with an urgent need to increase home food production, as imports of food and fertilizers were drastically cut. The area of land under cultivation had to be increased significantly and quickly. Under Defence (General) Regulation 49, the Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries was empowered to set up County War Agricultural Executive Committees ('County War Ags') to which the authority to increase food production was delegated. The Committees had powers to direct what was grown, to take possession of land, to terminate tenancies, to inspect property, and to organise mobile groups of farm workers. Much of the day-to-day work of the Committees was executed by district committees and sub-committees while the Executive Committee itself maintained a general supervisory role.

One of the first responsibilities of the County War Ag was to direct a ploughing-up campaign under which large expanses of grassland were prepared for arable cultivation. As a result, some areas of land that had not seen the plough since medieval or even prehistoric times was ploughed up. In June 1940, a farm survey was initiated to assist in this campaign, with the immediate purpose of increasing food production. Farms were classified in terms of their productive state, A, B, or C. These categories related more to the physical condition of the land than to the managerial efficiency (or otherwise) of the farmer. However, it was also vital to assess the ability of each farmer to play his/her part in the national food production plan. In cases of gross inefficiency or dereliction, land was taken into the control of the Committees and labour re-organised accordingly. By the early months of 1941 some 85% of the agricultural area of Britain was surveyed - all but the smallest farms.

Once the short-term objective of increasing food production had been met, thought was given to implementing a more general National Farm Survey with a longer-term purpose of providing data that would form the basis of post-war agricultural planning. Such a survey was seen at the time as a "Second Domesday Book" - a "permanent and comprehensive record of the conditions on the farms of England and Wales".

This project has considered oral history accounts of wartime production, the plough up campaign, and the role of the 'War Ags' in implementing change. In doing so we have generated alternative 'unheard' narratives, which extend and challenge our existing knowledge of the period.

Mapping the national farm

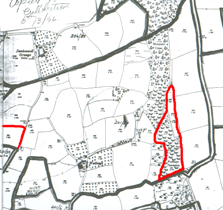

On one level the oral histories have allowed us to question the veracity of the National Farm Survey as an historical document. A map from the National Farm Survey was used in an interview with a 76 year old farmer from mid-Devon. Here, in recalling his family history, the farmer was able to directly challenge the accuracy of the boundary mapping of his family farm.

|

We've got a boundary wrong here, that boundary should be up there. That field isn't mine [...] That was Shaw's field next door...they have owned that for over a hundred years |

|

This bit was kept back when father bought it. They'd thrown a lot of timber there and in pulling out all the timber had broken all the drains, and father being fairly hot-headed said unless they put the drains right he wouldn't buy it...and they haggled over it for a while and they wouldn't put the drains right so father said you keep it |

Grade C = 'Lack of Ambition' ?

One of the most contentious aspects of the National Farm Survey was the grading of farms as either A,B or C, with the classification of B and C requiring further explanation. Often, this explanation involved an official's subjective assessment of the farmers themselves. On a number of these farm records 'lack of ambition' was given a reason for the perceived poor management of the farm. The following interview considered the labelling of one farmer, who the respondent had known well. In the passage he considers the extent to which the label of 'lack of ambition' reflects his recollection of the farmer.

I think they had a different notion of ambition than the farmers did at that time though. Frank was a farmer who made a living. He did that, he plodded on and made a good living. He raised eight children you know? Well he'd so much 'ambition' to do that hadn't he? I think he was just old fashioned you know...just because he didn't want to buy fertilizers they probably would have thought of him as having no ambition. He had a lot of land that could have been reclaimed, but only by today's standards. He knew very well that he couldn't afford to plough and lime, it would never have paid him. But the War Ags had the time and the labour, and the equipment you see? What they could achieve was very different from the small farmer. I don't think he lacked any ambition at all...after the war he bought more land and his family are still farming today. He was a well respected farmer - I don't think he could be accused of having no ambition.

(Mid Devon farmer, aged 78).

Offering Alternative Narratives

A major contribution to our understanding of the landscape offered by oral history interviews is what we have termed 'offering alternative narratives'. Here the oral histories have been used to provide an alternative stream of data in relation to land use and landscape change. These are able to inform us not only of the changing appreciations of particular landscapes and landscape features, but also to inform current conservation efforts by allowing us to challenge the nature of 'traditional' management which current conservation schemes aim to move towards.

Changing times, changing values

During the discussion of historic features on his land, a farmer in South Devon referred to a burial mound on his land. Within the discussion, the farmer (aged 82) explained the value of the burial mound as it appeared to him.

Are there any historical features on your land?

They tell me that we've got burial mounds. They've been to look at it...and it's been mapped out. We used to use it to load the cows for market. It's sloped up you see, so we used to back the lorry up to it and run the cows into the lorry

What is significant here is the way in which features take on different meanings to different groups over time. Here the priority of the farmer was the use of the land, and its features, to make a living from his farm. While opening up questions about the conflicts between agricultural production and landscape heritage, it illustrates the temporal changes and different meanings given to particular landscapes. Ironically, it was the Bronze Age burial mound's value as a cattle ramp that has probably protected it from previous mechanical obliteration! The oral history material allows us to reconsider the nature of current heritage conservation practices.

Changing landscapes: the case of hedgerows

Current conservation efforts encourage the replanting of hedges using 'traditional' techniques, often implying that the pre-war period was a sort of 'golden age' of unchanging 'tradition'. The oral histories and recollections of the two following farmers contest the extent to which hedges were well maintained in the pre-war period.

Oh yes, at the end of the war, father had a blitz and we went round and cut them all, but a lot of the hedges were like trees, all the way around...some of those trees had enough rings to be more than 70 years old [...] When I was a child I can hardly remember any hedges that were topped....we just hadn't got the labour to do it

(Farmer Aged 74)

Father and grandfather said hedging didn't pay, so they just left them, so when I took over they had 70 or 80 years growth on....They are definitely in better order than they have been for a hundred years, more than a hundred and fifty I expect

(Farmer Aged 79)

Other oral histories allowed a better understanding of factors in the decline of hedgerows. The oral history recollection below illustrates the symbiotic relationship between hedge cutting and the use of these trimmings to form the bed of hay and corn ricks. The second interview gives a broader scale picture of how hedgerow management fitted into the wider 'rotation' farming system of that time.

They'd got their certain field which they knew would grow good wheat, good barley, good oats...and it was all done on a seven year system. If you said you were going to plough a certain field on your farm, starting say from October, whatever wood that was on the hedges would be cut and used for firing, the hedge would be reinstated as a Devon hedge because there would be turf in the field wouldn't there? And you was allowed to use any turf out of that field because it was going to ploughed see? And you reinstated your banks. . then the field would be ploughed before boxing day that autumn, and in January, if they wanted spring wheat, he was tilled in January. If not, he was tilled late February, early March for oats and Barley and then the following year he would go into winter wheat, which would be tilled in November. ....the winter wheat would come off in early July, but then he would be re-ploughed and put to what we call "sheep's meat", which is kale, Swedes turnips. Then you'd have two years of Barley - that's five years. The sixth year would be oats, and the last year again would be barley with grass seeds under sown on it. In that seven years your hedge would have chance to re-grow from where it was laid and that. He would be nice and thick wouldn't he? And you'd get a nice stock proof hedge out of that....you also had a crop for firing. So the hedge would be managed with the field in the rotation....On a farm of say 150 acres, there would be two or three fields done each year...it was kept as manageable, an ordinary man could do the job all yourself.

(78 year old farmer, mid Devon)

The War, Mechanisation, and Landscape Change

The change from horse power to tractor

The war was undoubtedly a massive stimulus for the mechanisation of agriculture within Devon. The War Ags provided machinery which they held in pools, and which farmers were allowed to hire for use on their farms. The most common tractor used in the War time period in Devon was the Standard Fordson TVO, which was used in conjunction with the Ransome plough. While it has been documented that the demand for tractors, particularly from overseas, outstripped supply, a number of respondents highlighted a preference for farming with horses. In the following oral history excerpt, a farmer from South Devon recalls how changes in the nature of ploughing, caused by the introduction of tractors, had brought another problem of weed control.

When they [the horses] were ploughing they only took a ten inch furrow, so that the furrow was turned completely over, so the light was shut off and the weed died didn't it? When they started ploughing with the tractors, and they went to 12 and 14 inches, the mole boards weren't covering the ground as we call it. There would be a little bit left, that wouldn't get turned over. The furrow would break off and leave like a strip of land that wasn't turned - there is where your field got dirty as we call it. The weed wasn't turned over...they were trying to plough with a bigger fore and it wasn't turning over like the horse plough used to...that's why there was the need for all those weed killers.

Consent, dissent and indifference

The official records of the War Ag committees presents an unproblematic version of cooperation between them and the farmers as part of the plough up campaign. Little however is known about the precise nature of how these committees interacted with farmers, how local committees members were chosen and enrolled, and how certain areas were designated for ploughing. Oral history interviews have revealed that there was often a precarious relationship between the farmers and the 'War Ag' officials.

I remember the War Ag blokes coming. We were under two chaps....two retired farmers basically and they were run by a Ministry man who had an office in Kingsbridge. Some people took advantage of them. Some people disliked them and other people positively hated them....Most of them were retired farmers and they didn't have a particularly good reputation for husbandry when they were farming. When [an official] had a sale when he retired, there was dung houses right up to the windows....there was another one who was a bloody teddy grower, an horticulturist, and not a stock farmer...Another chap boasted in the pub, "I'm well in with WAEC, and if you want to get on you've got to be".

(Mid Devon farmer, aged 86)

They were farmers who were tied into things already you see? Like parish councils. They were known to the men at the top. When the War came they needed local eyes and ears so they took on these men. They were committee men - they knew how to talk a good fight so they got themselves in. To my mind they didn't have to know that much about farming. But they were given the power you see - you can see how the trouble began - it was farmer telling another farmer what to do.

(North Devon farmer, aged 86).

Custodians of the Countryside: Working the Land in Wartime Devon

The Second World War brought great changes in terms of who was working on and managing the land. Each person brings their own particular narratives of the war and the changes it instigated.

We were allowed the afternoon off school to go tatty picking. Because we were older boys and we were on farms, we used to go. We got money for it too. It wasn't much, but we got something I remember. We thought it was great excitement at the time. As children we were very much involved in the War effort.

(72 year old Mid-Devon farmer)

Reclaiming Land

The War Ags took a number of areas of common land into 'production'. Agricultural contractors and prisoners of War were used to plough this land and plant it with crops such as potatoes. A number of written histories refer to this 'reclamation' of land as a major boost in production. The two following extracts offer an alternative narrative of this process of reclamation.

There were potatoes which were clamped, and then left to rot. I don't know if they were forgotten about or what, but they were left there to rot.

(91 year old mid-Devon farmer)

If we had relied on what was produced from the common land we would have been in serious trouble. The land was ploughed but there was never much taken off them - they didn't produce much. If it hadn't been for the cheap labour they would never have been able to do it.

(85 year old South Devon farmer)

The plough-up campaign: Flash in the pan or catalyst for change?

While official records suggest that agricultural output was greatly increased as a direct result of the plough-up campaign, an issue raised from farmers' oral histories is the extent to which the plough-up campaign increased production in the longer term.

It broke the virgin land. They came with big crawlers and cleared all the furze off the land. Once the land had been broken it started to produce, and gradually we managed to increase the fertility of the land...we still use the land that was reclaimed.

(88 year old farmer, North Devon)

We ploughed land that should never have been ploughed you see? It was wet and boggy land that couldn't really grow much when it had been ploughed. As soon as the pressure from the War Ags was off, after the War, it went back to grass and has stayed that way ever since. I don't think it ever paid back the effort that was put into ploughing it really

(91 year old Mid-Devon farmer)