In December of last year (2016), I completed the final stage of the digital archive and dissemination for the The Rural Settlement of Roman Britain project. The first publication and (revised) online resource were launched at a meeting of the Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies at Senate House of the University of London.

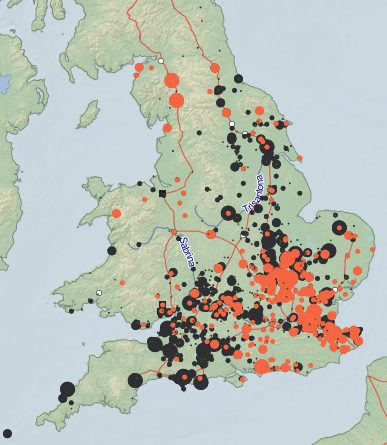

I’ve written previous blogs on the project, so won’t repeat myself here too much. Suffice to say that the final phase publishes the complete settlement evidence from Roman England and Wales, together with the related finds, environmental and burial data. These are produced alongside a series of integrative studies on rural settlement, economy, and people and ritual, published by the Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies as Britannia Monographs. The first volume, on rural settlement, has now been published, while the two remaining volumes will be released in 2017 and 2018.

The existing online resource has been updated both in content and functionality: the project database is available to download in CSV format, and most key elements of the finds, environmental and burial evidence have been added into the search and map interface. Hopefully the dissemination of the data in these forms allows re-use of this fantastic dataset in a variety of ways and, I hope, by a variety of users.

As with previous posts on this project, I’d like to say how much I’ve enjoyed working with the team at Reading and Cotswold. Producing an online archive and formal publication in tandem and in such a short time is no mean undertaking. I’m particularly happy/impressed with the determination by the researchers to make their data openly available at the earliest opportunity. Hopefully this is a benchmark that others will aspire to reach. A debt of thanks is also due to all those organisations that assisted the project, particularly the HERs of England and Wales who provided exports from their systems and aided the team at Cotswold with access to fieldwork reports. Finally, I’d have been lost without the awesome Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire created by Johan Åhlfeldt. At an early stage it became clear that creating any kind of ‘baseline mapping’ of Roman archaeology (combining NMP + HER data for example) would be problematic – both in terms of technical overheads and copyright. To do something on the scale of the EngLaId project’s ArcGIS WebApp simply wasn’t in the scope of the project! Johan’s work was thus timely and extremely useful in providing a broad backdrop of Roman Britain in which to compare the project results.

The rationale behind much of the interface work was to act as data publication of an academic synthesis and not to get tied down in building something akin to a Roman portal. Throughout the project we’ve been at pains to point out that this is very much a synthesis and interpretation of the excavated evidence in relation to a research question. Not a complete inventory or atlas of every Roman site. Indeed, it became clear that as soon as the data collation had been completed 31st December 2014 for sites in England and March 2015 for sites in Wales), it was effectively missing all the discoveries made in the following years. Thus although providing broad context was necessary in this case, if someone wanted to know everything about the Roman period (including sites not excavated) from a particular area they’d be best off consulting the relevant HER.

This in turn leads onto the $64,000 Question which I was asked at every event around England and Wales (including the final one in London). “What plans are there to keep this database updated”? Without wishing to appear pessimistic, I would always answer “None”. Aside from the logistics and finances of keeping a large database as this constantly updated, there’s also the fact that this is a very subjective synthesis of a much larger resource. To my mind, the key question is how do we make it easier for other researchers to build on this and have academic synthesis of a period or theme happen on a more regular basis. One of the answers to this is surely access to data, especially the published and non-published written sources. This isn’t really radical, and indeed increased access to data is being explored and recommended by the Historic England Heritage Information Access Strategy. The work of the Roman Rural Settlement project has many lessons to inform these strategies, some of which will form future papers by the project team. Out of curiosity I’ve undertaken my own analysis of the project database and ‘grey literature’ sources (a term I don’t like!) and the OASIS system but will save that for a separate blog post. ..

At the post-launch meal I did end up asking the team a rather cheesy question of “which is your favourite record”? The responses were often based around the level of finds, or in the relative level of information the site could add to a regional picture. My answer(s) were perhaps a little more prosaic, for example I really like records such as Swinford Wind Farm (Leicestershire) which has fieldwork reports disseminated via OASIS, and a Museum Accession ID. However my heart veers towards 42 London Road, Bagshot (Surrey): the site of my very first experience of archaeology as a somewhat geeky 16 year old. The site was never published, and thus it’s great to see it live on in this resource and with a link to the corresponding HER record to (hopefully) allow users to go and explore the wider area. Perhaps even to undertake their own research project. To my mind, to stimulate further work large and small that would be a great legacy of the project.

Tim