(Re)analysis of Wood from Dorestad

At the end of the seventh century Dorestad, situated near present Wijk bij Duurstede in the central part of the Netherlands, functioned as the centre of a flourishing North-Sea trade network (Jansma & Van Lanen 2016).[1] Located near the rivers Rhine and Lek it was important to the Frisian- and Carolingian world and many other parts of north-western Europe. Excavations at Dorestad started in the 1960s and have continued for decades. Dendrochronology was applied to its water wells and foundation piles in 1972-1974 at the Institute for Wood Biology (now Zentrum Holzwirtschaft) at Hamburg University, in 1990 at the Dutch national archaeological service ROB (predecessor of the current Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands (RCE)), and in 1996-1997 and 2009-2011 at the Netherlands Centre for Dendrochronology/RING Foundation. The early research at Hamburg University already showed that many oak barrels re-used as water wells in Dorestad had been assembled in the German Rhineland (Eckstein et al. 1969). The material archive of the Dorestad excavations at present is stored in the depot of the National Museum of Antiquities (RMO) in The Hague.

Starting in 2011 the dendrochronological potential of Dorestad was reassessed in order to develop additional geographical and chronological information about the Dorestad excavations and about the trade and exchange network(s) in which Dorestad was a key player. The work consisted of:

- Analysing a subset of uninvestigated yet dendrochronologically-suitable oak timbers and reanalysing available dendrochronological data from Dorestad in order to increase the chronological resolution for this site;

- Creating an inventory of wood finds from – and dendrochronological results pertaining to – Dorestad in order to facilitate reanalyses and new research of this material;

- Comparing dendrochronological data from exogenous oak (Quercus robur/petraea) excavated in Dorestad to other Early-medieval datasets, in order to identify common exogenous provenance and to improve our knowledge about the network(s) in which Dorestad was a key player;

- Storing and unlocking new results using the DCCD repository (see Section 5.3; Jansma et al. 2010; Jansma 2013), in order to facilitate more follow-up research.

Twelve well-preserved and as yet unanalysed oak samples were selected for dendrochronological analysis, focussing on relatively early structures in Dorestad. None of these samples contain sapwood, which implies that successful dating only can result in terminus post quem (tpq) dates of the calendar years in which the trees were felled. Of this group two samples could be dated absolutely, yielding tpq dates after AD 489 and 643.

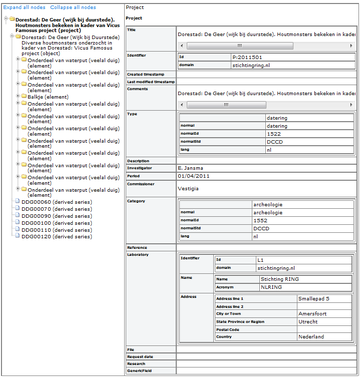

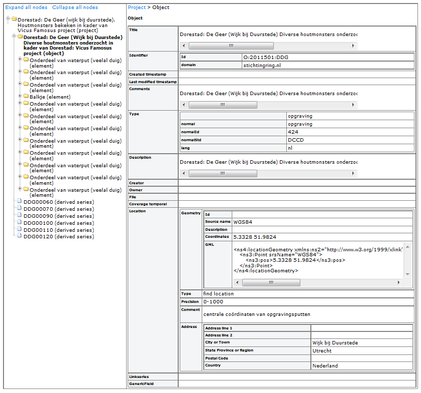

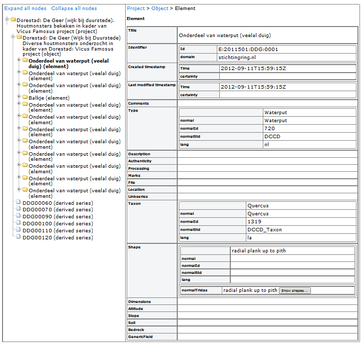

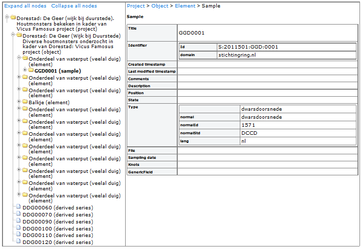

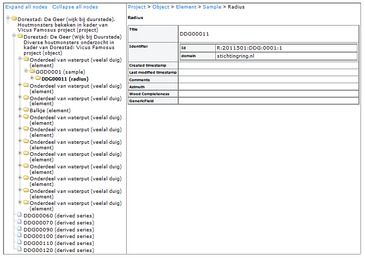

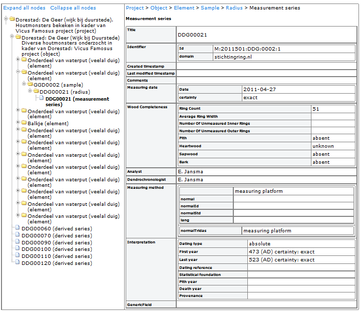

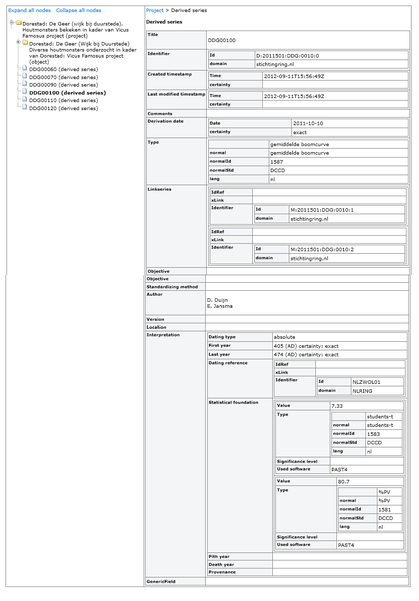

Sample metadata were administrated using the MS Access format TRiDaBASE database following the requirements of TRiDaS (table 1; Project planning and requirements and File types (whilst creating, working with, and processing data); Jansma et al. 2010).[2] Using TRiDaBASE the metadata were exported to XML, which was uploaded to the DCCD together with the measurement series. The results were stored in the DCCD using the project identifier P:2011501 (Figs. 1-7), with the default level of access set at ‘value (download)’. This access level ensures all DCCD members have full access to and can download the project file including the measurement series.[3]

Although the reanalysis of existing data did not result in new dates, it did enable the identification of elements derived from the same individual tree. In addition we noted a marked discrepancy between the end dates of staves from the same individual barrels (up to a hundred years; Jansma & Van Lanen 2016). This indicates that the dendrochronological date of barrels cannot be determined with any accuracy by studying only a limited number of staves, which due to financial considerations, amongst others, is quite common in archaeological research.

Table 1: TRiDaS-based metadata administered within project P:2011501 (also see Figs. 1 to 7).

| Project level | Title; identifier; identifier domain; created timestamp; last modified timestamp; comments; type; investigator; period of investigation; commissioner; category; laboratory |

| Object level | Title; identifier; identifier domain; comments; type; description; location, and the following location subfields: source name, coordinates, GML, type, precision, comment, address |

| Element level | Title; identifier; identifier domain; created timestamp; last modified timestamp; type; taxon; shape |

| Sample level | Title; identifier; identifier domain; type |

| Radius level | Title; identifier; identifier domain |

| Measurement-series level | Title; identifier; identifier domain; measuring date; wood completeness and following subfields: ring count, pith, heartwood, sapwood, bark; analyst; dendrochronologist; measuring method; interpretation and following subfields: dating type, first year, last year |

| Derived-series level | Title; identifier; identifier domain; created timestamp; last modified timestamp; derivation date; type; linkseries; author; interpretation and following subfields: dating type, first year, last year, dating reference, statistical foundation (and subfields: value, type, used software) |

[1] This case study in part summarizes and/or quotes Jansma & Van Lanen (2016).

[2] TRiDaBASE was developed for dendrochronological metadata management and interaction with the DCCD repository (Jansma et al. 2012b) and can be downloaded from http://www.tridas.org/tridabase/. At present TRiDaBASE only runs under 32 bits, which limits the use of this application.